March 21st 2023, San Salvador.

Leaving Nicaragua was not as difficult as I feared it might be. The various officials at the frontier were, well, as they should be — polite and efficient in their work, and I and the bike passed through their hands without incident, unlike arriving into the country a few days earlier. When I came to leave, I gave in when approached by a frontier fixer and went along with his instructions, contrary to how I usually do these things. I have an instinctive reaction against people who swarm around me when I arrive at a border crossing, telling me (without having been asked for help) to do this and that, and park here, not there, and “come, come, this way…” etc etc. But this man was a little less pushy than others, and my resistance was low. He was also good. First off, he led me to the photocopy guy — a sweetie huckster shop at the side of the road with, yes, a photocopying machine behind the counter. He was doing a roaring trade too, as border crossers got their documents copied, which the officials would demand shortly. For me, it was the driving licence, passport and bike registration form.

Then it was into immigration and customs, copies taken, originals examined and — whoosh! — “pasar”, I was cleared to proceed. My friend had one final service to offer. Wait here, he indicated on the street at the Nicaraguan side of the river bridge that marked the spot, at Guasaule, where Nicaragua became Honduras, and visa versa. As I did, he ran off towards the bridge and disappeared for a few seconds into one of the tiny shops, before reappearing and running back to me. He indicated that that was it, all done, I should have no problems now! I fingered $5 in my pocket and gave it to my friend, thanking him for his help. He was pleased and thanked me but said he had paid €20 just now (this was the run into the shop, I believe) so I wouldn’t have to deal with that either. It was not clear for what this payment was made (if it was!) but I got out €20 to reimburse him.

On reflection, I think he did well out of our encounter!

On the other side of the bridge, Honduran police had a first look at everything before I actually got off the bridge itself. It is at moments like this that you fear the worst — what if something is not right and I am turned back and have go through the whole rigmarole again? But all was well; he waved me on. Next, the immigration lady was charm herself and then customs went smoothly as well. The setting was slightly odd: an ugly building straddled the road right at the end of the bridge on the Honduran side. It was quite a long building, creating a tunnel effect. Customs was at the far end of the tunnel, after immigration, and there were several people hanging about — the usual freelance currency traders (the US dollar is the currency in Honduras, something I had not realised), a few people who appeared to be fruit or fish traders, and a couple of women with an empty slingsby trolley — what it carried or was about to carry remained a mystery. As we all waited, one of the slingsby women made great fun of me and my bike and, when the customs guy said all was in order and gave me the crucial papers that would allow me leave Honduras, I said goodbye to her with a full embrace and a big hug. That got whoops and jeers from the others. And she loved it!

The first thing that hit me about Honduras was the thought “Oh God, I’m back in Peru!” The dumping and filth as the roadside was incredible — as bad in many instances as Peru was. Great screeds of rubbish — plastic bags, bottles, paper, nappies and organic matter — in huge mounds lining the roadsides. I just cannot understand how, or rather why, people do this to their own community. Even without adequate rubbish collecting, there’s no excuse for this.

The second thing that hit me was solar energy farms! There were quite a few of them west of a place named Nacaome, where I biked past big spreads of solar panels all soaking up the sunlight and feeding electricity into the national grid. Why there are not more in the whole region, I don’t know because there’s a hell of a lot of sun going to waste. In 2015, Honduras was the second biggest producer of solar electricity in Latin America, the largest output coming from the Nacaome region. In fairness to Nicaragua, they too have invested heavily in renewals, which now account for about 60 per cent of energy produced and the country is exporting to its neighbours. Renewals account for 98 per cent of Costa Rica’s electricity needs — also pretty impressive.

Honduras is a very narrow country on its southern flank by the Pacific — just 130 kilometres border to border and the coast is wrapped around a bay named the Gulf of Fonseca. I decided to head in that direction and get a seaside perch for the night. I ended up in a place named Coyolito, a jumping off point for Isla Tigre, a visually striking volcanic island maybe a kilometre offshore, that looked very beautiful as the sun began to sink below the horizon. Poor old Coyolito was in a bad way, however. The side of the alley on the road down was used as a garbage tip and the town itself, sitting on the edge of the bay, and looking across to Tigre — Tiger Island — did its level made to make the least of its beautiful setting. The backs of the houses were facing the water, and there was rubbish everywhere, especially along the tidal high water mark and a dry stream bed leading to it. An open drain, a channel maybe a foot wide and with a dangerously buckled grill, missing in parts, looked like it carried much more than just water.

Still, it was getting late and I asked a man at the slipway for the small boat ferries to the island whether there was a hostel. Yes, he said, pointing to a place in the middle of the huddle of buildings. I could see first floor patio and, on its side, just make out the word hotel. That would do nicely, I thought.

The entrance to the hotel was through a garage, protected by a wide metal bar gate. A small boy opened it for me and I was soon greeted by a late middle aged man who was evidently drunk. As he was telling me that, yes, he had a room, a strikingly good looking middle aged woman rushed forward eclipsing your man. She had a great mop of hair, all curls and plumped up. She was in beach wear, a bikini of sorts as far as I could make out, and had over her shoulders and wrapped around her, one of those bright, multi-coloured diaphanous silky flowing throws that failed, as perhaps it was intended, to conceal entirely. Her shoes were peep toe wedge heels that looked as though they were missing a couple of feathery pom-poms. She was small in stature but had a personality to compensate for that.

She sailed towards me and swatted your man aside and showed me the room. It was, well, basic but it would do. Yes, they had beer — served on the terrace above — and there were indications of food. I was in like a shot.

After a shower and securing the bike, I went up to the terrace and met the other members of staff — a man, in his late 30s perhaps, who wore a baseballs cap back to front, a T-shirt and jeans that looked as though they had not seen a washing machine since about 1957; and a woman in her late 40s who seemed actually to run the place. She busied herself ferreting around here and there, and if not, giving directions to Baseball Cap — usually to bring more beer. I was the only hotel guest.

Diaphanous Hyacinth, she of the peepy toes, was in a hammock, where she stayed for most of the following five or six hours, tap-tapping on her phone or chatting excitedly. She had a big Coco Chanel, gold chain and padded latex handbag that appeared to be stuffed with money. She directed the Ferret and Baseball Cap on beer and food runs as she and I chatted. She had a really big personality and there were lots of interesting aspects to her life and background but, ultimately, I think she was sad inside. Despite her charm and good looks, I felt there was also an big emptiness. She owned the hotel but was about to lose it. She had a business in the capital and three grown up children but her marriage was kaput after 26 years.

We chatted and chatted, drank lots of beer and then I went to bed around midnight, getting up next morning at 7am. When I went to check the bike, Ferret was at the iron bar gates, on the outside, absolutely blind drunk evidently having been up all night, god known where but wherever it was, there was drink involved. Hyacinth emerged from her room looking like three quarters of a million dollars and got back into a hammock. Baseball Cap, who had slept fully clothed in the upper terrace hammock, was roused to unlock the gates so I could escape. But this had the added complicating effect of letting Ferret back into the compound where relations with Hyacinth deteriorated rapidly.

I hit the road. . .

Crossing into El Salvador, I headed straight for the capital, San Salvador and a hostel named Cumbres del Volcán Flor. It was quite difficult to find because Google maps was not very precise and the place didn’t exactly advertise itself with a big sign but it was everything I could want. It is managed by two very pleasant young people, Andrés and his assistant, Saraí. The thing about travel is the stuff you don’t know but find along the way. I knew of course about El Salvador’s appalling civil war from 1979 to 1992. A colleague and friend from The Sunday Times, David Blundy, was killed here in 1989 and I left my wife Moira in labour with our about-to-be-born son, Patrick, to attend his funeral at Highgate Cemetery in London, something I am reminded of at each of Patrick’s birthdays! I had no idea, for instance, that El Salvadoran architects were significant design pioneers throughout Central America and made a major impact on their own capital city.

Hostal Cumbres del Volcán Flor is an example.

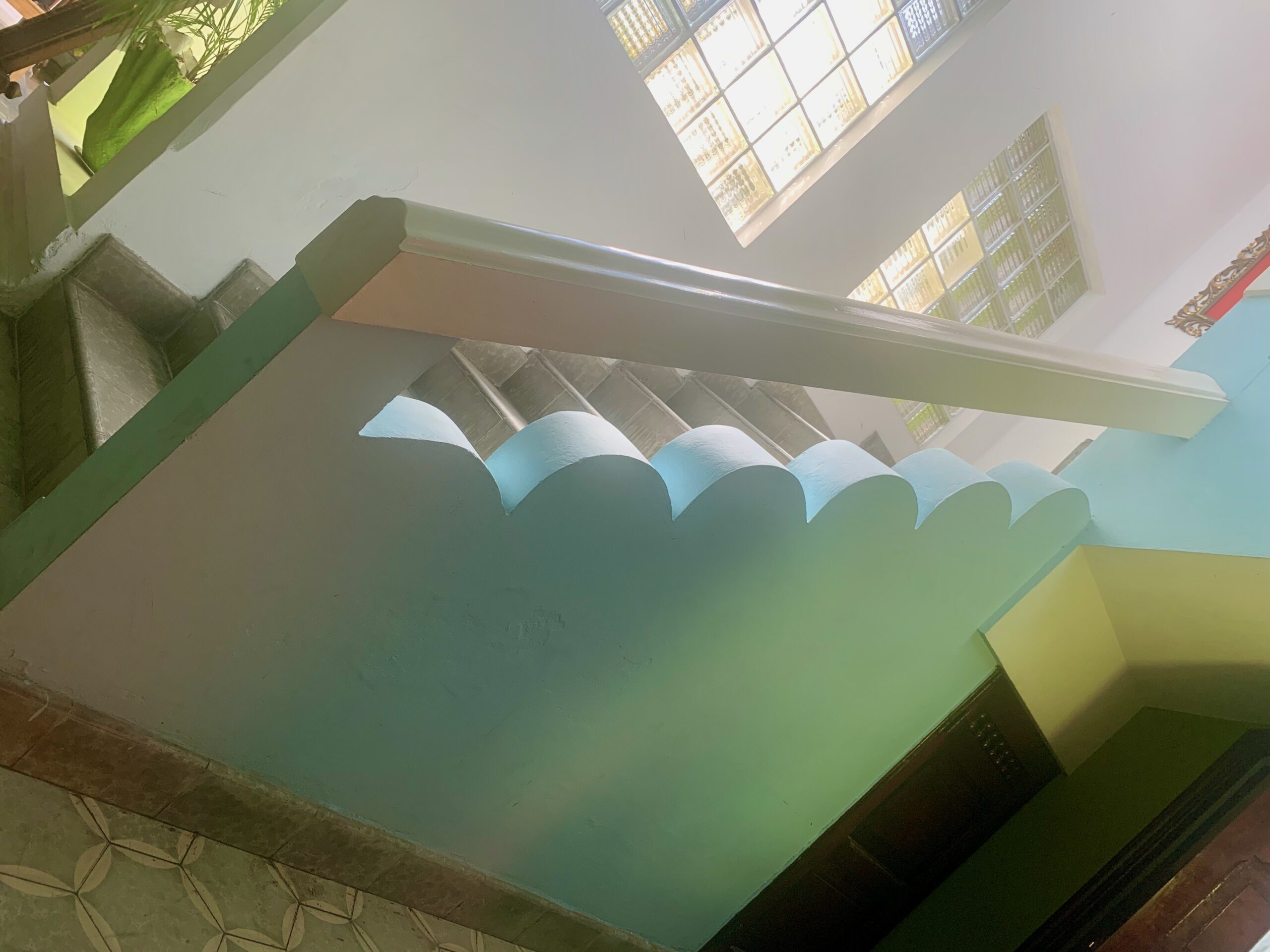

It was built in 1950 but has a 1930s Art Deco feel to it. The first owner, for whom it was built, was a man named Carlos Dordelly. He sold it immediately to a Dr Cesar Emilio Lopez, an obstetrician, and it was known thereafter as the Lopez Mansion. The doctor died in 1958 and, for the next 40 years, the place was home to a number of women, including his widow Lola, the last of whom died in 1997 aged 100. The current owners bought it for $160,000 from the estate of the doctor and Lola’s daughter, Bertha Lopez, and had to do a lot of work on it because of the effects of what is described, rather quaintly, as “deferred maintenance” — ie jobs that weren’t done when they should have been. These included a new roof, new plumbing and wiring, and a new kitchen. The place had to be completely redecorated and furnished, but using, in some instances, old Lopez family pieces, including two distinctive wooden rocking chairs, plus a timber dining table and matching chairs and wicker seating for the hall. The whole place has a light, airy feel to it, with a gentle and welcome breeze flowing into a plant-filled atrium and out again.

There’s a photo of the widow Lola in the hall reception area and also a painting of Bertha. There’s a tiny bit of Frida Kahlo intensity about Bertha’s appearance. She never wanted to leave the house, apparently, repelling family efforts to get her to sell. It still feels homely, in part due to the furniture and, I think, a sense that the Lopez family influence endures.

The current owners are Malcolm Collins and his wife, Gladys Hernandez. Malcolm’s a bit of a character. For a start, he’s 77 but looks like he’s in his early 60s. Like most of his hostel guests, he lives in jeans and T-shirts and spends much of his time sitting at an elevated desk (an old bar from the Lopez family era, he tells me) in a corner of the hall, beavering away online. Malcolm is from the US — “I grew up in LA but had my teens on an alfalfa and cattle farm near Mexicala, about five miles the Mexican border,” he says. Gladys, to whom he has been married for 44 years, is originally from El Salvador but spends most of her time at their other home in Los Angeles, while Malcolm oscillates between there and El Salvador. He is a retired maintenance engineer for an LA corporation and bank that ran data centres. Despite his surname, he doesn’t think there’s an Irish connection.

“My family came to America in 1632, from Maidstone to Virginia,” he says. “Collins is an odd name. The English Collins is derived from Nicholas.”

I didn’t know that.

“El Salvador was a very prosperous country right up until the 1970s when the wheels came off,” he explained. “Only now it is beginning to get back on its feet.”

The source of wealth was coffee, the price of which exploded, says Malcolm, when the US entered the second World War and coffee consumption similarly went through the roof. The oil crisis of the 1970s saw a fall in prices, with knock-on economic consequences for El Salvador, and then the collapse of centrist politics.

Malcolm tells me that Dr Lopez was married twice. Newly qualified, he and his first wife, who was pregnant, went for a break in the mountains where she, then in her early 20s, began haemorrhaging. Inexperienced, he was unable to prevent her death but vowed never again to be so impotent as a doctor. He went to France to train as an obstetrician and became the most renowned in El Salvador, founding a maternity hospital that continues to this day.

I love the way old houses are full of stories and Malcolm is a diligent curator of the story behind San Salvador’s Lopez Mansion, lately become an attractive and welcoming hostel for travellers, young and slightly less so.

You haven’t mentioned anything about Bukele.?

Another great family story, beautifully told, Peter! And, yes, the portrait of the widow Lopez has something of Frida Kahlo about it. Don’t know whether it’s on your list or probably too far off your route, but Frida ‘s and Diego’s house and gardens in Coyoacán/ Mexico City is a wonderful place of art, peace and serenity to visit.

Thanks; will have look where that is and, if possible, drop by!

Peter, I have enjoyed this. My wife Juanita is from El Salvador and we have always enjoyed our visits there over the years. It’s a beautiful country with lots of problems

Would like to have seen more… but the road beckoned! But yes, nice place and nice people!