After Tucson, I rode straight west towards San Diego, California, spending one night camping in Yuma which is on the border with Arizona. That evening, something happened that I believe is a regular occurrence there — a mighty sandstorm blew up from further west. Visibility was down to about 100 meters and the effect made the busy freight trains of the Pacific Union line linking Los Angeles and Texas seem all the more ghostly as, during the night, they wailed their sirens at every level crossing but you could see nothing of them, just hear that mournful sound. Next day, I saw the source of the storm: about 80 kilometers of pure sand desert that got whipped up in late afternoon winds caused, I assume, by the intense heat of earlier in the day. It happens regularly, I was told.

San Diego appeared suddenly after I crossed the Cleveland National Forest, which was more upland scrub than anything else. Rather than enter the city, as time was cracking on and I needed to find somewhere to bed down, I skirted around it, finding myself soon on Highway 101, El Camino Real and the Pacific Coastal Highway. At times, they were all one and the same road, at other times they diverged into separate entities. It was a little confusing but the route is terrific, either way.

A little bit like the Wild Atlantic Way on our west coast, El Camino Real links places along the southern California coast that have existed for a very long time and are of Spanish heritage. The road has been there for yonks too; it’s just been given a name. Highway 101 is also the coastal road, and is sometimes El Camino Real at the same time. Every now and then, the road becomes the Pacific Coastal Highway, which is also known as Route 1. Confusing? A bit but who cares? The way north is clear enough and it skirts through settlements that are pretty and coastline that is beautiful. So far, I’ve only gone from Oceanside through San Clemente, Dana Point and Laguna Beach and the overwhelming characteristic is upmarket style in everything from shops, to cars, to homes and money — lots of money — and lots of retirees.

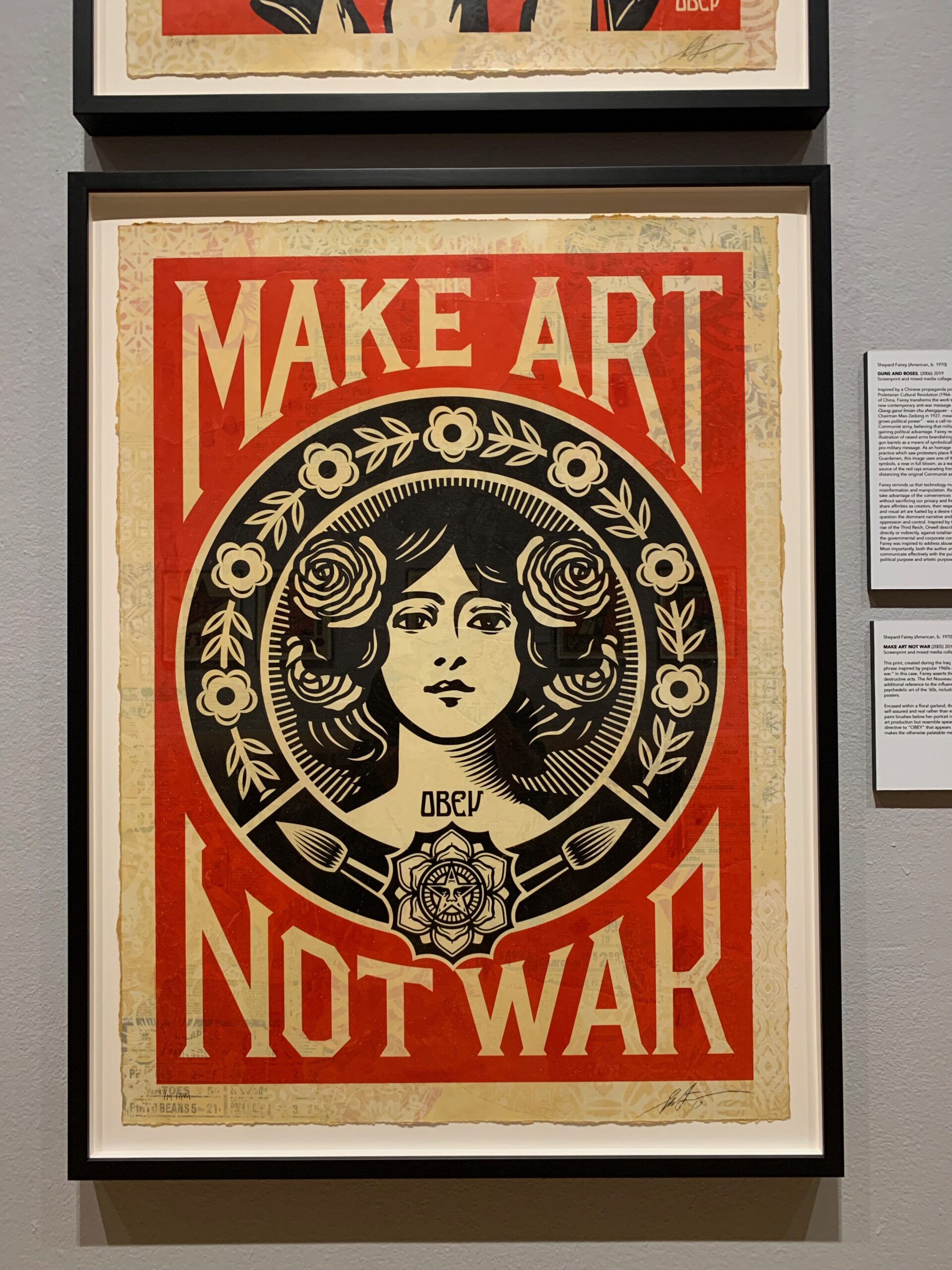

At Laguna Beach, a big sign caught my eye: Dissent, it said and with it was a large poster in red, black and cream of a female face that reminded me a little of the Czech art nouveau painter and graphic artist, Mucha. The sign was on the side of the Laguna Art Museum and I thought I’d have a dekko.

Inside was a wonderful exhibition of posters by Shepard Fairey, the American artist who achieved much wider fame with his “Hope” poster of Barack Obama which came to define (visually) the former president’s 2008 campaign. The exhibition at Laguna Beach is entitled Facing the Giant — three decades of dissent: Shepard Fairey. I think I counted 30 posters and they are really striking — mostly in the same style and using only red black and cream but striking all the same. Several highlighted women’s issues, others the cause of African-American equality, others still general inequality. They have something of the flavour of socialist realism about them or, as the gallery puts it, “his bold, iconic images always convey a clear message, often depicting the struggle of oppression as a human experience and celebrating those who fight for change”.

I thought they were wonderful and well worth stopping for. There were many other beautiful, more traditional paintings in the gallery too — landscapes and coastal scenes in oil.

I’ve been camping almost every night since I left Texas because the cost of hotels is so high — rarely under $80 a night for the cheapest — but the RV parks that cater for mobile home users (ital) and (ends ital) tent campers are getting more and more rare. When they do, the price varies hugely too. I’ve been charged anything from $7.50 to $40 for a night and conditions vary too, from awful to slightly less awful. Another option are State Parks and National Parks, most of which cater for tent campers, with toilets and showers. Along southern California’s coast there are some in locations that hoteliers would kill to develop but thankfully cannot because the lands are publicly owned and preserved.

Last night, I camped in Crystal Cove State park, a large undeveloped area between Aliso Beach and Huntington Beach that caters for RVs, campers and hikers. It cost $55 which is pretty steep merely to pitch a tent. However, the camp site is on a bluff, maybe 150 feet above the coastal road and has panoramic views out to the Pacific and up and down the coast. There is a large military presence at Oceanside, with a huge Marine Corps base and also a navel base. Helicopters come and go, and, earlier in the evening, I watched the landing of an Osprey, the weird Marine Corps fixed wing plane whose propellers can swivel to a vertical position, effectively turning it into a helicopter.

I cooked dinner beside the tent, ate and drank wine, watched the sun set and went to bed.

At 4.30 the wind and rain came — pitter patter on the tent; a lovely feeling of being safe and out of the wet when you are tucked up in a sleeping bag. It always reminds me of playing with my sister Jane when we were children. We would put a blanket between two single beds to make a sort off cave-cum-tunnel, our den for the afternoon. The tent stood up to it all perfectly and, come the morning, the sun was out by 9 and I was sitting writing this.

One of the slightly odd things about California is the place names — Bakersfield, San Jose, Long Beach, San Bernardino, Big Sur and, of course, Hollywood. What’s odd is that you catch yourself thinking “Oh yeah, I know that place . . .”

And of course you don’t. It’s just the movies.

The above appeared in The Irish Times Weekend on April 6th 2023 section and on irishtimes.com. Since filing it, I learnt more about Laguna Beach and Crystal Cove.

The area around Crystal Cove used to be privately owned, by a family named Irvine. A company run by the family began life in the wholesale and retail grocery in San Francisco, branching out later into property. James Irvine and his younger brother William were Irish. They came from Co Down and went to the US in the mid-19th century when much of Ireland was in the grip of the famine. They worked initially in New York city before, in the 1850s, being lured to California by the gold rush. When his business began returning healthy profits, James Irvine invested heavily in coastal property in southern California, eventually creating a large coastal estate around what is today Laguna Beach — in fact, the family at one stage owned one third of all the land in Orange County, one of the wealthiest in California. Not bad for a couple of migrants from Co Down. In 1937, James Irvine II, son of the first James, set up a family foundation and through this, much of the property was handed over eventually to the State . . . to be enjoyed today for its public-access beaches, camp and RV parks, and hiking trails.

In the 1920s and 1930s, some Japanese families leased farm land from the Irvines, which they worked successfully. They built small beach hut-style timber homes for themselves at Crystal Cove, right on the beach where a small stream enters the sea. Today, these too are publicly owned and are gradually being restored and are available to let. They are quite beautiful. Sadly, the Japanese people who created them did not fare well. After Pearl Harbor, which caused the US to enter the second World War, they were rounded up and interned, losing their leased farmland and pretty homes for ever.

Here’s what they look like today . . .

Peter, you are an inspiration to all those who wish to wander. Camped right next to you at Kenney Grove County Park in Fillmore. we shared stories and travels and I’m sure we were all amazed by your journey as much as you were by our silver trailers. Please keep in touch and have a safe and fabulous journey through Canada and Alaska. I promise we will see you in Dublin for more stories and a few pints of Guinness. Take care my friend. Michael and Nancy

Thank you both very much! I enjoyed your company too and hearing all about your love for Airstreams. Look forward to that Dublin hookup… Best to you both — Peter

Hello Peter – Enjoyed some scintillating and lovely talk with you around the campfire in Fillmore California. We are off to a Bluegrass music festival next weekend in Parkfield . So lucky to be retired and out of the fray. Wishing you bon voyage. R

Bluegrass music? Now that’s tempting for a minor diversion cross country! Have fun… Best — Peter