14th June 2023, Nelson.

Nelson’s old post office, a solid three storey granite and red brick building with a turret, stands on the corner of Vernon and Ward streets, bang in the middle of the small town/city in British Columbia. Most of the 1902 building is given over now to a museum that tells the story of Nelson and its surroundings. The current post office lives next door, in part of a modern block called the Grey Building. But the old post office hides what until very recently was a secret (sort of): a basement that was a Cold War bunker, capable of sustaining life for several weeks . . . if America and Russia started dropping nuclear bombs on each other.

The bunker was built in 1964, one of over 50 across Canada. They were known as Diefenbunkers, after the prime minister of the day, John Diefenbaker, on whose orders they were built. Nelson was something less than a key strategic Cold War location in Canada, though it did have a lot of telecoms workers, but Diefenbaker went there a lot for fishing and the suspicion is that the small city got its bunker just in case he was around when Armageddon arrived. The bunker is open to the public since October 2018 and the first thing that strikes one on entering, or struck me at any rate, is the ludicrousness of the official advice at the time.

A door off the pavement, sandwiched between the old post office building and the Gray Building, whose private owners also exercise control over the bunker, opens to a descending stairwell. The way down is lined with 1950s style posters featuring two characters, Bea Alerte and Justin Case. “Disaster may never occur here,” says a finger-wagging Miss Alerte, “but if it does, civil defence may save your life.” The tone of the posters is only centimeters away from the ridiculous advice to women and children, all those Cold War years ago, to hide under the stairs/kitchen table/school desk in the event of an atomic bomb and the follow-on shockwave.

At the bottom of the stairs are a pair of showers through which one must pass to enter the bunker. The showers would, apparently, wash off any nuclear or chemical contamination caught topside.

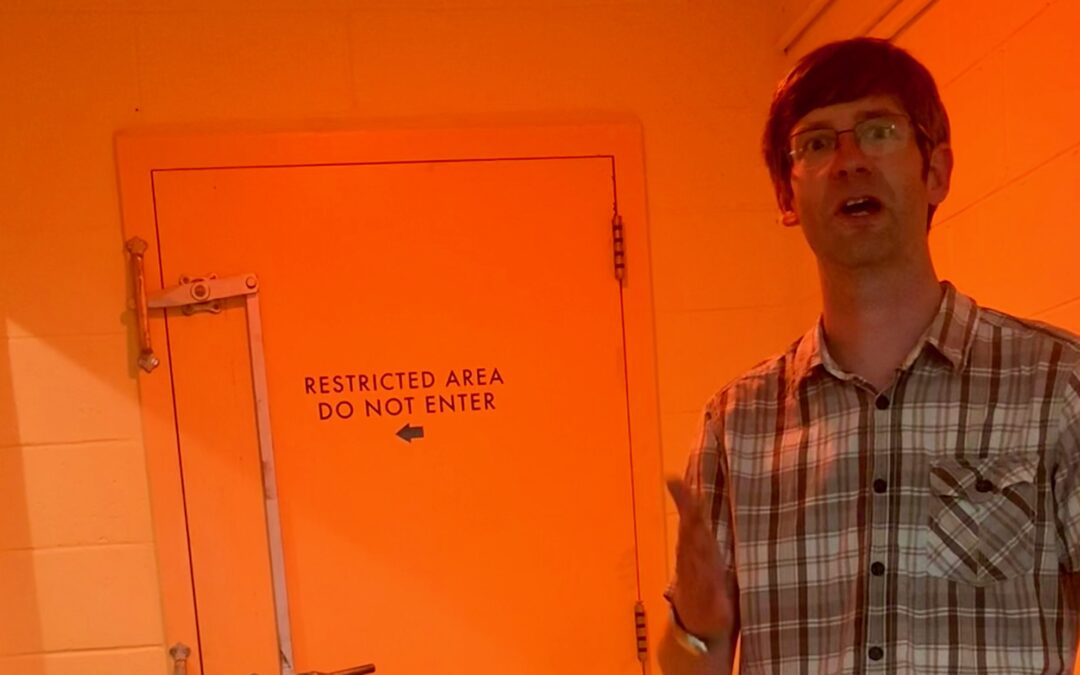

The museum’s wonderfully relaxed Archivist and Collections Manager, Jean-Philippe Stienne, led myself and a handful of more local visitors through the bunker. It was built to house about 70 designated people, he said. About 80 per cent of the bunker dwellers would be men, and 20 per cent women — reflecting the breakdown of genders across the key sectors at the time. All told across the country, such bunkers were capable of accommodating around 8,000 — but only key personnel. No wives, husbands or children. In fact family members were not even supposed to know if a relative was on the list of those to enter a bunker when ordered. The overall aim of the bunker network was to ensure (1) a continuation of government in the event of an attack and (2) a community and state capability of responding to the consequences — however naive that might seem — if there had been a full-on global thermo-nuclear eruption.

The people selected for entry were all key officials: emergency first responders, civil and military defence personnel, medics, radio operators, skilled workers such as mechanics and electricians, and others with communication skills, and key players in regional and national government. So from 1964 onwards, there was a fairly large group of Nelson townspeople who knew all about the bunker under the post office and the circumstances under which, one day and in secret without saying anything to their families, they would be expected suddenly and by alert to go there, knowing what was about to happen. It seems highly unlikely that such a thing was kept as secret as intended.

After the showers, one steps into a large and austere main room, perhaps 12 or 14 meters square, off which was a communications room and various others, including a kitchen-cum food preparation area, a big clunky metal box of kitchen implements, male and female bunk bed rooms, a room with Swedish-made diesel-powered generator, and a water tank room with three huge metal tanks.

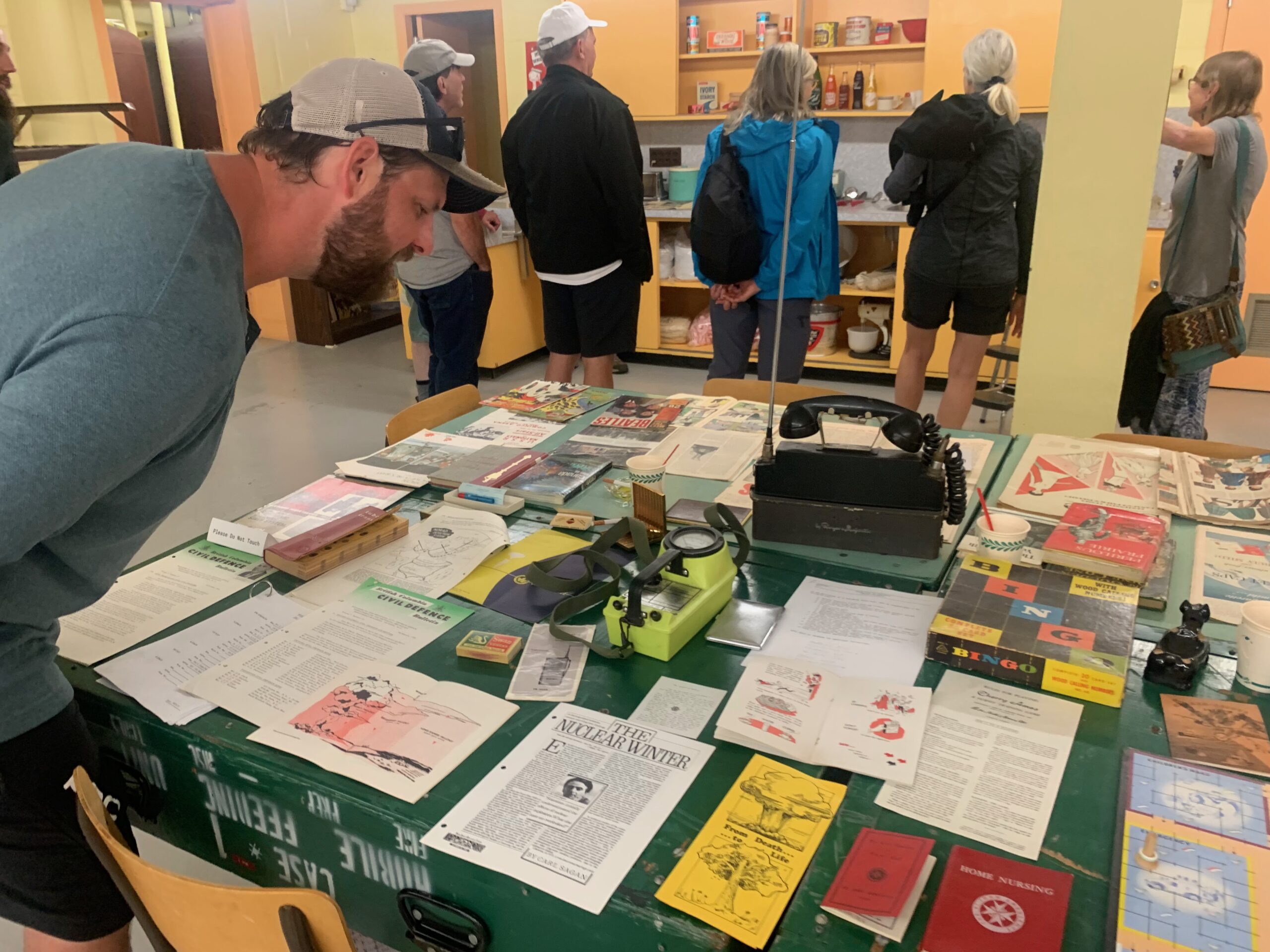

Jean-Philippe reckoned they held enough for perhaps six weeks’ survival. However, the place had enough food for just two weeks — what happened after it ran out was unclear but food was stockpiled inside the bunker until the 1980s. On a table there is a display of various items relevant to the period, books and pamphlets, a field telephone and a radiation-measuring geiger counter (an original from the time was actually found in the basement when they began exploring it and is also on display). There are several display cases filled with items, and wall mounted posters, that attempt to explain the Cold War to today’s visitors, many of whom may not have lived through that epoch of mutually assured destruction, or MAD, when, bizarrely, the nuclear arms race terrified both sides into a sort of impotency and kept the peace.

Full public confirmation of the existence of the bunker came in 1974 through a report in a local newspaper. And yet, somehow, there seems to have been a sort of collective amnesia about it, though people working above it all knew, apparently, there was a basement . . . even if none of them went down there or effected to know anything about it! The current museum moved into the post office building in 2006 and, some years later when discussing logistics and storage, a board member who happened to have been one of the key personnel selected to enter the bunker in an emergency, advised his museum colleagues to, ahem, take a look downstairs, as it were. So now, several of the rooms, notably the formed dorm bedrooms, are used to store museum artifacts not on display, as well as boxes of documents relating to the town’s history and business, while the rest of the bunker is open to tourists. A wall map shows civil defence zones across British Columbia, all related to worst case scenarios of the Cold War that, thankfully, never happened.

The museum began private tours in 2013 and some groups, such as civil defence, used the space for meetings after that. It was not until October 2018 that it was opened generally to the public, with visits today hosted by the knowledgeable Jean-Philippe and colleagues at the museum staff. It really is quite a weird place — exposed pipes and a low ceiling — as befits a bunker, breeze block and concrete painted walls. Overall, there’s a severity and utilitarian feeling down there that suits, I guess, the times that created it in the first place, and the cold but necessary calculations that lay behind it.