Puente Linda, February 28th 2023.

After my few days with the migrants in Necocli and Capurganá, I made a dash for Bogota, feeling that it was time to progress my own journey into Central America. The road south from the Gulf of Darién was good and passed through some pleasant lowland countryside — lots of banana and oil palm plantations and quite a bit of cattle ranching — of which there isn’t that much generally in Colombia. After 400 kilometers, I leapt at the first Ibis Hotel I saw in Medellin — €50 for a night isn’t bad for clean, modern hotel with a working shower and it meant that next day, I was off early for what should have been the final five hour, or so, run to Bogota.

But it ended up taking two days, nearly broke my spirit but looking back now, I wouldn’t change a thing about it.

Mr Google Map suggested highway 56 for a fairly direct run from Medellin to the capital and so I took it. Somewhere around 100kms outside Medellin, the road began to take on the characteristics of a lesser used road and I began to wonder. It had just one lane in either direction, was not at all busy and I suspected the main highway between two such important cities would be bigger than this. Before Sonsón, the road started to rise into mountains — nothing unusual in that in Colombia — riding up steep sided valleys with sharp peaks, before plunging down again, and all the time through dense jungle. And then, at a small town named Nariño, the road disappeared altogether. I rode through the town and out the other side whereupon a paved road veered left but, straight on, highway 56 presented itself as a stony, muddy track, the sort of track you’d see leading from an Irish farmyard off into the fields behind. I stopped and asked a man walking by “Esta la camino a Bogota?” — my Spanglish for “Is that the road to Bogota?” Yes, he said, that’s it. “Directo!”

And so I set off. The road began with an easy enough, if steep hill down, and quickly disappeared around a bend and I felt certain that the proper road, the main route to Bogota for god’s sake, would resume just around the next bend. But it didn’t and very quickly, highway 56 became a consistently stony road, sometimes firm and relatively flat, but most of the time scored by horrendous gullies regularly on either side of the median. There were numerous cones of mud and rubble half blocking the way, the result of landslides caused by rain loosening the land above. Sometimes on acute bends, the outer edge of the road had collapsed but it carried on, winding its way up and down the increasingly dominant mountain landscape.

I went through the process of trying to decide whether to call a halt and turn back (which would have been physically difficult) but, as is the way, each kilometer I progressed, the idea of turning back became less appealing, while carrying on had little to recommend itself either. In the event, I carried on, my spirit gradually wearing down, and with it, a growing sense of alarm and fear: I was getting deeper and deeper into mountainous terrain — and I mean really steep-sided mountains that were all jungle covered and, initially at least, had few signs of human habitation. Looking at a good map later, I see that I traversed the south facing shoulder of the Cordillera del Tigre mountain range, passing between two peaks, one standing at 3,323m and the other at 2,700m. But at the time, it just seemed like a jungle mountain trek without end! Whenever there was a gap in the vegetation, the views of the mountains and valleys below were spectacular. I stopped to take photos of them but didn’t manage to get really good ones of the road because, on the worst stretches, the last thing I’d think of would stopping to take a picture — I just wanted to get through and remain upright. Biking along tracks that regularly become little more than a dry river bed requires intense concentration and is hugely stressful, for me at any rate. You stand on the pegs, lean forward and, crucially, must not lower the revs when coming to place that looks really difficult — the “road” may have fallen away on one side, there may be a 50 meter stretch of large boulders, rocks the size of footballs say, all mixed in with gullies and mud and flowing water. But the only way to get through is to approach it with determination, keeping the revs up, stay in first gear and, well, just go for it. Easier said than done. . . And despite the narrowness of the road, and the sometimes precarious grip it has on the side of the mountain, occasional busses and trucks lumbered their way along it as well, some with reckless abandon. All a biker can do is stay out of their way!

After 20kms of this, the road ballooned into a flat triangle of open space, where three small valleys met and a wide, fast flowing river surged through. On one side of the triangle, there was a long colonial-style two storey building, with ground and first floor verandas wrapped around it, and a large mural running the length of it. On another, there was a restaurant and hostel; and on the third, backing onto the river, a large hotel. A hotel! I could hardly believe it. The Santa Isabel, which had a bamboo construction theme to it and was two storey at the front but four at the rear thanks to the land falling down to the river, boasted a swimming pool and promised food and a bed for the night. I needed no encouragement to call it a day and get myself in there.

The woman who ran it, Diana, was immediately great fun. Warm and slightly flirty, she served me a cold beer and said I could help myself to more from the fridge. She then gave me dinner — a big bowl of hearty bean soup, followed by a steak, tomato, rice and fried banana. There was another couple staying at the hotel. The woman looked French for some reason but in fact she and her husband were both Colombian and they spent most of their time playing cards. There was another man too but he just wandered about offering huge avocados to anyone who wanted one. They were delicious. The dining area overlooked the pool — three connected pools in fact and well up to large hotel standards — set back from the river, a raging torrent after a night of thunder and downpour. Its muddy waters crashed around large boulders and tumbled under a steel bridge — the Puente Linda, from which the place took its name.

That night, and the following morning, I had long conversations with Diana and her husband, Alcibiades, a similarly warm fellow, though thankfully not as flirtatious as his wife. It turns out that all around Puente Linda, the lands were littered with anti-personnel landmines, and that the riverbed beside the hotel was rich in gold.

The mural on the long building opposite included an image of someone with a mine detector and, separately, referenced the Halo Trust, the Scottish demining NGO, patronised by the late Princess Diana and funded today by, among others, the US, Canadian, Norwegian and New Zealand governments, as well as by Irish Aid, the Irish government’s international development aid programme. Earlier, as I was leaving Nariño, I passed a large complex of low buildings and a sign that announced the Halo Trust and, to be honest, though I noted it, I didn’t think much about it, so concentrated was I on the damn road!

Were there mines around here, I asked Alcibiades. Yes, he said, lots — about 2,000 in fact. It turns out that this area was a hotbed of guerrilla activity by Farc, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, dissolved in 2017 following a peace agreement with the Colombian government. Over 260,000 people died in the five decades-long conflict and seven million were displaced. Farc, which professed itself to be Marxist-Leninist, financed its operations by taxing Colombia’s drug gangs, by kidnapping people for ransom, by bank robberies and extorting businesses. It had long-standing links with Sinn Féin and the IRA, a fact established in 2002 by US Congressional investigators. They found that the IRA had received at least $2million in drug money from Farc, apparently for training members in bomb making. In August 2001, two IRA explosives experts, Jim Monaghan and Martin McCauley, were arrested in Bogota, along with Niall Connolly, the Sinn Féin’s representative in Cuba. Convicted of travelling on false passports but on bail while the authorities appealed their acquittal on the training charges, the three fled the country. A former police inspector alleged he had seen McCauley with Farc members in 1998. If true, perhaps some of the IRA’s “expertise” was used by Farc in an atrocity committed in Nariño that Alcibiades told me about, aided by a journalistic history of the conflict, rutasdelconflicto.com.

In July 1999, 300 Farc guerrillas, led by a woman, Elda Neyis Mosquera García, known as Karina, attacked the town. During a 30 hour assault, 16 people, including four children, were murdered, and another 16 were kidnapped, including eight police, seven of whom were held captive for two years. The town’s police commander was “executed” formally in the town plaza. Using car bombs, gas cylinder bombs and mortars, the guerrillas demolished the town hall, a number of shops and houses, and the police station — a total of four blocks. After the massacre, half the people left the town, reducing its population to 9,000. The place has never fully recovered.

All these years later, Alcibiades said it still wasn’t safe to walk freely through the jungle, though many of the mines placed there by Farc, often crude homemade devices, had been cleared, he said. I asked him about another panel of the mural, one showing men panning at the river. Was there plata (silver) there, I asked. No, he said, “oro” — gold!

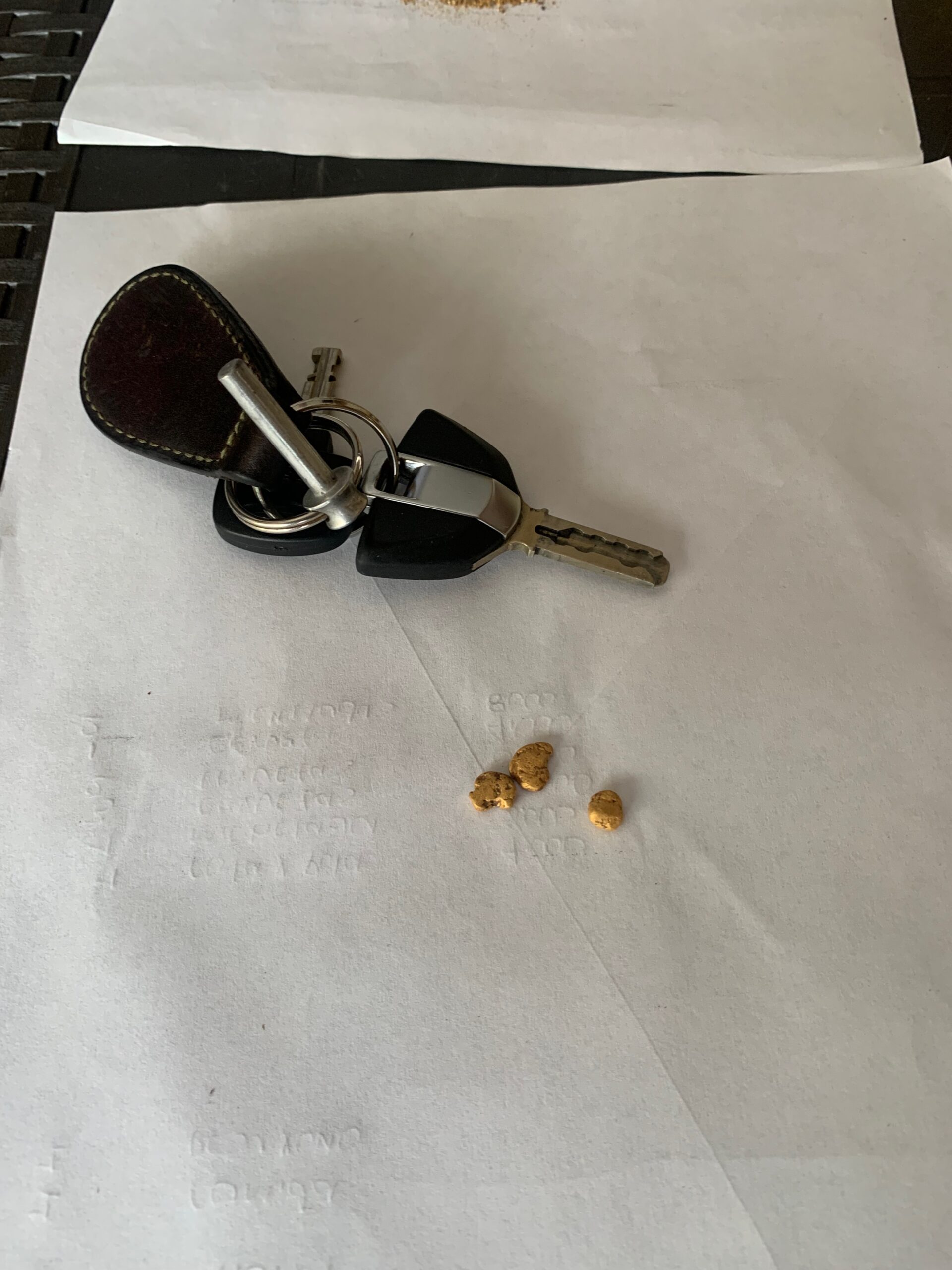

And with that, he rushed into his and Diana’s bedroom and rummaged through a bedside chest of drawers, returning with four small plastic vials, their lids taped shut. He placed two sheets of white paper on the table and turned the contents of the vials onto them. And there it was — pure gold, some specks not much more than dust really, but several small nuggets, each about the size of a lentil or split pea. Alcibiades also had a tiny weighing scales and he put the contents of one vial onto it — 3.3 grams, it read. I asked how much that was worth? He said about 660,000 pesos, or $130. We both stared at the gold in wonderment and laughed.

Soon, I was off again, over the bridge and up the rocky road for more energy-sapping thrills but no spills, thankfully. I had been promised that the paved road resumed at Norcasia but in fact, it reappeared just before then, at a village named (like several others in these parts) Berlin. And was I glad for it! By this stage, I was running out of cash and petrol, but in Norcasia I stocked up on both and made the final dash for Bogota.

Great adventure Peter and really interesting you are giving us a really sense of your travels. Thanks again and fair play.

Thank you! Just about half way now….

A very enjoyable read taking us there with you, onwards and upwards

We could feel the tension of this blog from here, Peter!! Great descriptions!