April 18th 2023, in Austin, Texas.

Sitting at a set of traffic lights in Fredericksburg, another biker pulls up alongside me and we have the conversation — where from, where going etc etc? “I’m going for a coffee,” said the other guy. Can I join you, said I, and with that, Mario Werner (53) from Heuston in Texas, via the Black Forest and Hamburg, is parking his Honda Africa Twin on Fredericksburg’s Main Street and I’m doing the same.

Fredericksburg is right in the middle of what Texans call their Hill Country, a slightly upland region west of Austin but we’re not talking the Andes here — these hills are no more than 150 meters above the plains below them. But the region is topographically pleasing; a mixture of rolling hills covered in small trees or scrub and also farm land, much of it given over to vines producing grapes for gewürtzraminer and albariño wines, as well as some reds. Fredericksburg was founded in 1846 by 120 German migrants who named their settlement after Prince Frederick of Prussia. In all, some 28,000 Germans settled in the Hill Country around that time and the German influence is very pronounced even today. The word “haus” is used frequently by the up market tourist shops that line Main Street where Mario and I stop for coffee in a cafe festooned with German memorabilia and specialising in those cinnamon pastries Germans love. The fact that Mario is originally from Germany is just by the by. He came to America first as a student and later settled in Atlanta, then Miami and then Texas working in logistics for a shipping forwarding company before defecting to one of their customers based in Heuston. He is married to a local and has a 16-year-old daughter. He wouldn’t dream of returning to Germany. “I just love their friendliness,” he says of the Americans. “People are always welcoming you.”

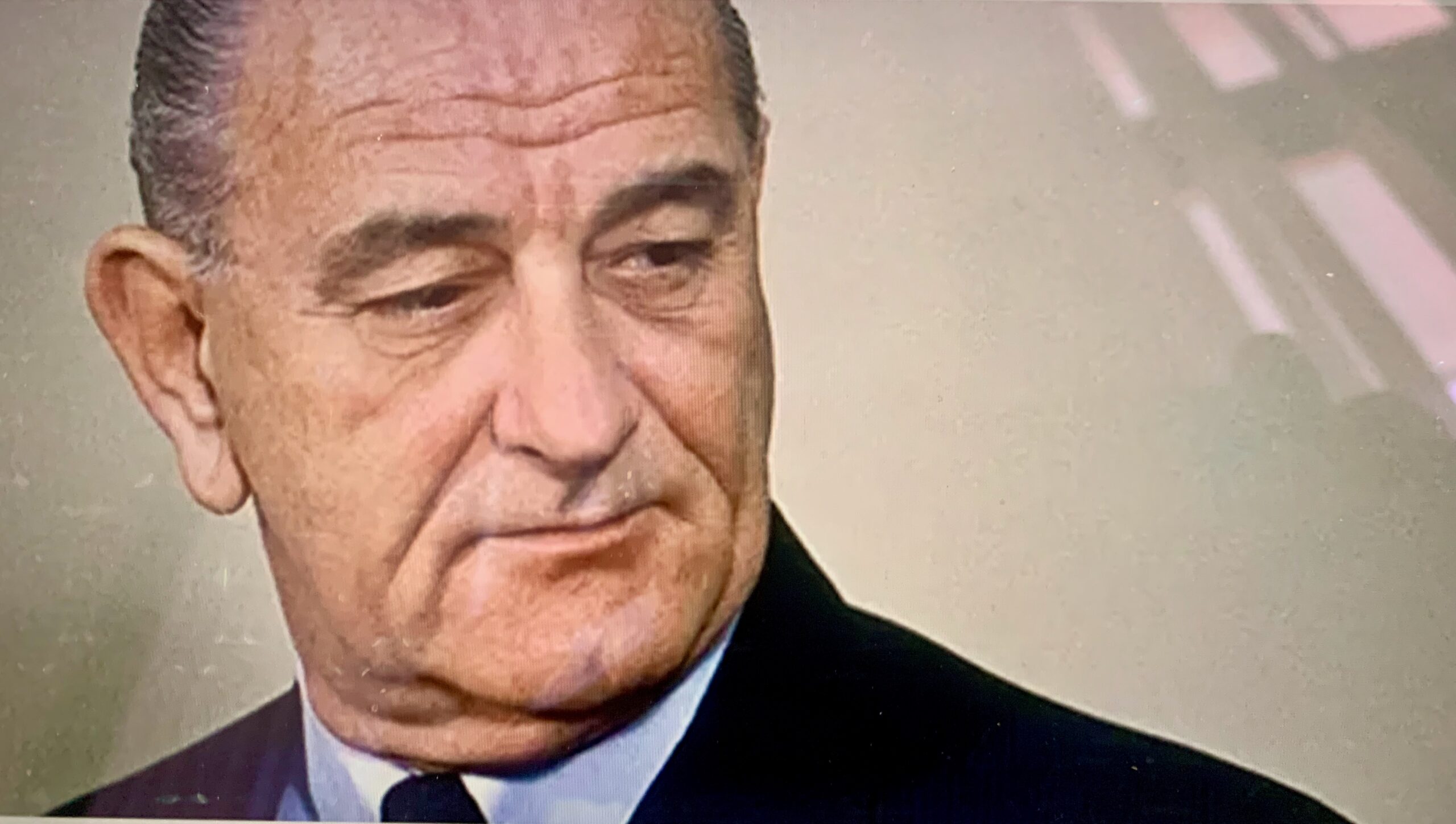

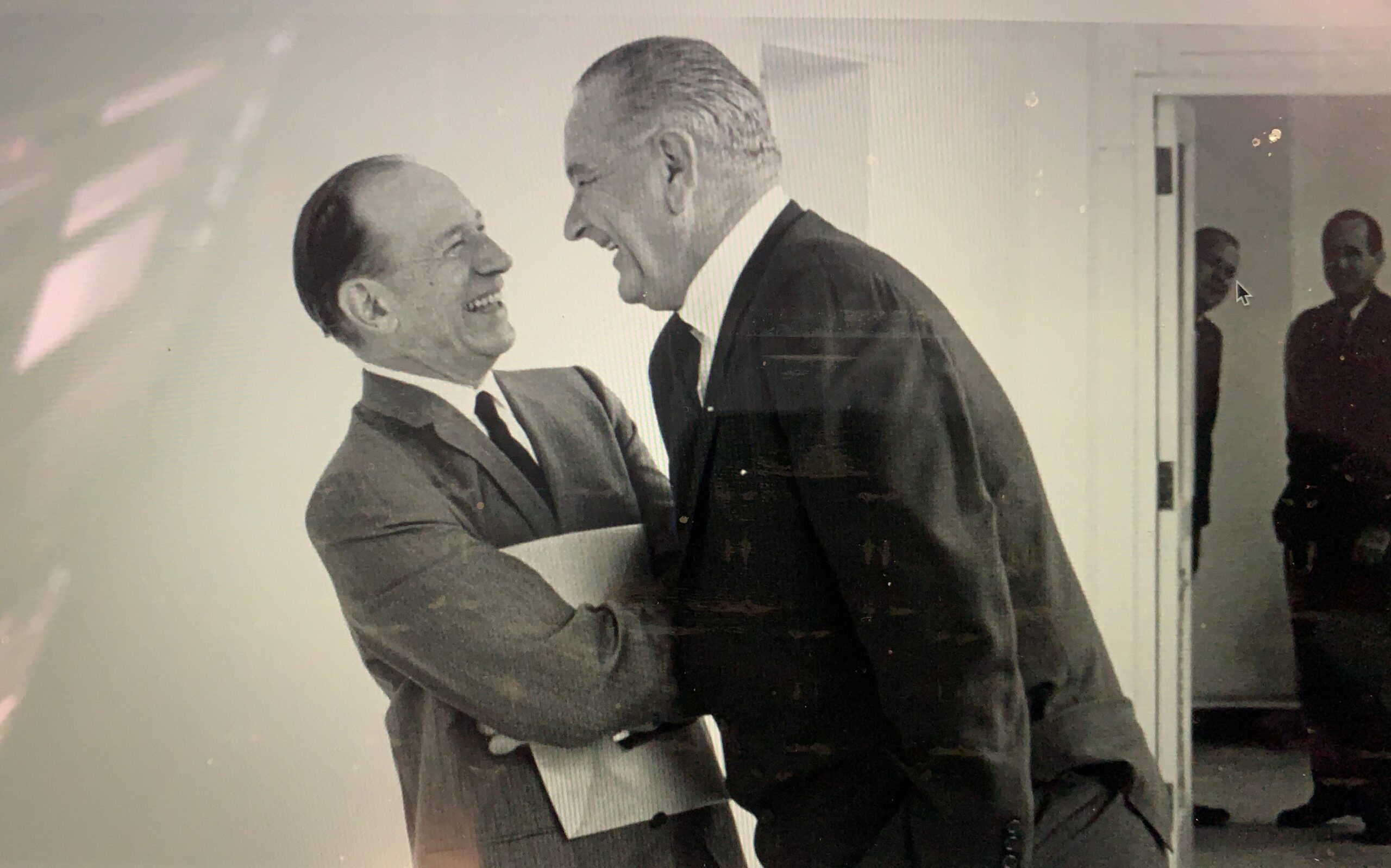

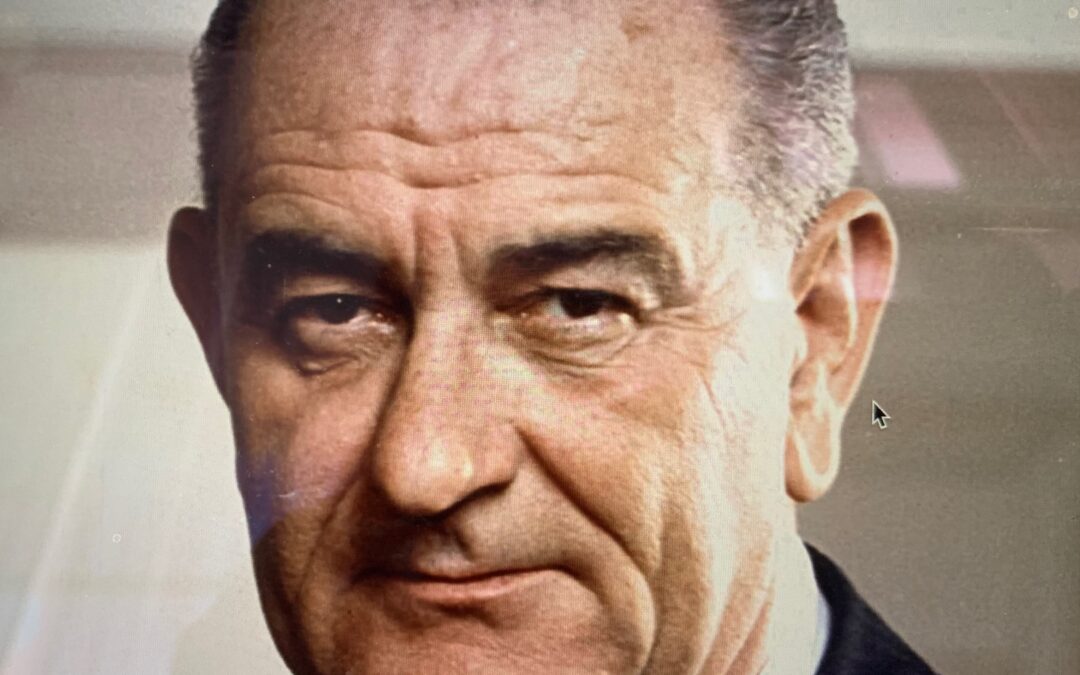

The whole German thing came as a complete surprise to me. But then so too did the other major feature of this part of Texas — the legacy of President Lyndon Baines Johnson and his wife, known as Lady Bird Johnson. I knew Johnson was Texan but hadn’t realised he was from the Hill Country. For many non-Americans of my generation, Johnson is associated with one thing above all else: the ghastly error that was America’s involvement in the Vietnam war, with all its carpet bombing, Agent Orange chemical warfare and the wasted lives, there and in the States. He is also remembered as something of a rough diamond given to occasionally crude if colourful quips — “Well, it’s probably better to have him inside the tent pissing out, than outside the tent pissing in”, he said once of J Edgar Hoover, director of the FBI who was antagonistic to many of Johnson’s civil rights reforms.

But first, Lady Bird.

Riding through the Hill Country, one is immediately struck by the wild flowers lining just about every road in the area. There are great big drifts of them, blues, yellows, whites and reds, on the sides of the roads and in the medians separating lanes. And because they are there, so too are flocks of butterflies. The visual effect is really striking and quite lovely. This is not the first thing one thinks of when one thinks of Texas and it is all down to Lady Bird. She was fanatical about wild flowers and loved seeing them in drifts on her and President Johnson’s farm near Fredericksburg which was gifted to the State after they died, he in 1973 at the relatively young age of 64 and she in July 2007 aged 94.

She was from eastern Texas but a friend in Austin introduced her to LBJ when he was working as a congressional aide. On their first date, which was to the still standing grand Victorian pile of a hotel in the city named the Driskill, he proposed but she demurred for 10 weeks before succumbing, drawn “like a moth to a flame”, as she said later. Her lasting legacy is the Highway Beautification Act, which her husband signed into law in October 1965. But she was the driving force behind its passage through Congress, cajoling and brow beating Congress members and Senators to support it. Her belief in nature was total: “where there are flowers, there is hope,” she once said. At the time, many American highways were lined with grotesquely outsized advertising hoardings that literally blocked out the surrounding countryside. The Act banned them and promoted the planting of wild flowers along the sides of the highways. Signing the act into law, her husband said: “We have placed a wall of civilization between us and the beauty of our countryside. In our eagerness to expand and improve, we have relegated nature to a weekend role, banishing it from our daily lives. I think we are a poorer nation as a result. I do not choose to preside over the destiny of this country and to hide from view what God has gladly given. . . Beauty belongs to all the people.” And he turned to her after signing, giving her the pen he had just used.

LBJ was born into poverty in a very modest wooden cottage on what became the LBJ ranch. His mother’s midwife was Augusta Sauer, descendant of one of those early German settlers. His father, a cotton trader who went bust, was also a Democratic Party member of the Texas house of representatives. LBJ’s own legacy as an environmentalist is on display at their ranch, now a State park and where both he and Lady Bird are buried, only a few feet from that wooden house where he was born.

It remains a working farm with a herd of Hereford cows but many of the fields are given over to tillage and to wild flowers. Signs by the road through the ranch tell of the nearly 300 conservation measures he introduced, including the Clean Air Act of 1967, and laws on waste disposal and reducing the use of pesticides.

But it is not until one visits the LBJ presidential library in downtown Austin that the enormity of his legislative legacy is really brought home — well, to me at any rate. That Vietnam millstone — “I can’t win and I can’t get out,” he once said despairing of the war — overwhelms. It is not just the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“America must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice” he said of ending segregation; “justice and morality demand it”) or the follow on Voting Rights Act of 1965 (“It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote”, he told Congress, appealing or them to support a ban on all literacy tests and other restrictions used to deny African-Americans the vote). Both Acts helped transform US society. He used the murder of Martin Luther King to ram through legislation banning discrimination in the allocation of housing on the grounds of race, colour, religion or national origin. He got a law passed banning racial discrimination for jury selection. He introduced Medicare, food stamps for the destitute and launched what he called “an unconditional war on poverty”, overseeing the largest fall in poverty, from 20 per cent to 12 per cent, of any American president.

It was all part of what he called his Great Society vision of a fairer, more socially just America, which he outlined in a speech at Ohio University in May 1964. “It is a society where no child will go unfed, and no youngster will go unschooled . . . where no citizen will be barred from any door because of his birthplace or his colour . . . where peace and security is common among neighbours and possible between nations,” he said.

To that end, he signed into law numerous Acts expanding education and access to student loans. He began his working life teaching impoverished Mexican Americans and the experience is said to have embedded in him a belief that education was a route out of poverty. Other environmental measures included expanding national parks and wilderness trails, the wild and scenic rivers act; a freedom of information act and a public broadcasting act; safety acts aimed at children, traffic, highway and mines; and gun control . . . the list goes on and on.

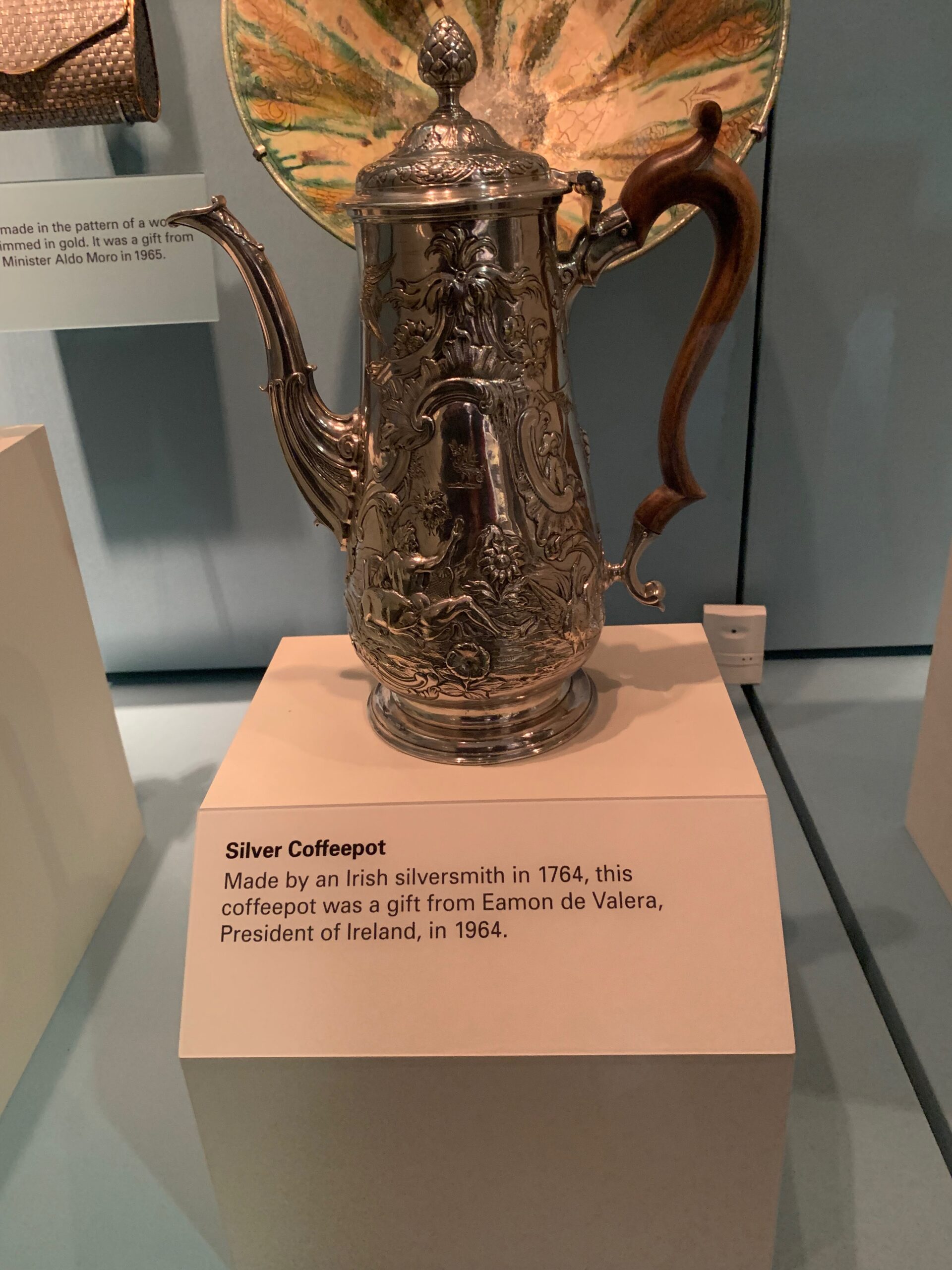

The library, the core of which are all his presidential papers, a rich source for historians, is full of political ephemera. Among the items on display is an Irish silver coffee pot, dating from 1764, a gift from President Eamon de Valera in 1964.

Some of the most moving exhibits are recordings of phone conversations, including with Martin Luther King and Jackie Kennedy, the slain president’s widow. In one, he talks to her after the November 1963 assassination that propelled Johnson into the presidency in the first place. You stand there, phone cupped to your ear, listening to Johnson trying to comfort her, telling her she is welcome to come to the White House any time, and her almost girly, high pitched very feminine voice replying, thanking him. The library includes many photographs, including the famous one of him being sworn in as president, Jackie standing beside him, wearing the jacket stained with her slain husband’s blood. Let them see it, she said.

The library and the story it tells is quite extraordinary. Johnson, who spent virtually his entire political life in Washington, as a Congressman, then Senator, then vice-president to Kennedy and on into the White House itself, knew how to get his way by political arm twisting and bullying, using his height and considerable physical presence to overpower opponents, and emerges as a hugely consequential president with a legacy blighted by a war he could not win or end. When you look at his legacy in the round, I don’t think any president since has had such a profound and lasting impact on US society, with the possible exception of Ronald Regan, whose legacy includes enriching the already rich and the efforts, sustained by others to this day, to undo much of what Johnson achieved. “If courage remains our constant companion, we shall overcome,” Johnson said urging support for his civil rights measures and adopting the language of the civil rights movement.

I stopped into a garden center to buy some wildflower seeds for two friends I am visiting in Austin, Paul and Melissa Vlek. In the shop, four middle aged ladies behind the counter got chatting to me — “I just love yaw accent,” said one. I explained where it was from and what I was doing and all that. “Ireland is on mah bucket list,” said one of them. “Well,” I said, your President Joe Biden has just been with us for four days. Well, that was about as welcome as stepping in dog dirt. Boy, they sure don’t like Joe Biden down here and my impression is that that is a very, very widespread view of the current president, and indeed the Democratic Party as a whole.

Which has me wondering: how in God’s name did this place produce a man like LBJ with such a burning reforming zeal and a list of legislative achievements, so many of them designed to redistribute wealth and help the less well off? Johnson’s politics come from a political ethic that would seem to be anathema to how many of his fellow Texans see the world now. Today in Texas, I couldn’t see them going “all the way with LBJ” . . . or even a small part of the way.

Truly excellent and thoughtful piece, young Murtagh.

Perhaps the real loss, Peter, is the loss of nuance, the reduction of politics to a zero-sum game in which one is either one thing or what is perceived to be its direct opposite.

I endorse your comments on LBJ, although I would add two points of, well, nuance. Reagan had great moral qualities (as had Margaret Thatcher), and I don’t think he was a racist. In these two respects he was indeed diametrically different from the most recent Republican occupant of the White House. Also, I believe Obama will come to be seen as the most consequential President since LBJ, not only because of who he was as a human, but also for his success in preventing US, and global, economic collapse in 2008, albeit in cooperation with the UK and, especially, the EU and the ECB.

Your energy is an inspiration to me, young man. I don’t know if your route takes you through Chicago, but if it does check out the Obama Library if you will. It contains a stunning photograph of a young African-American man in the long pond at the US Capitol, taken by Sam Mcdonald, a Scottish journalist who worked with the Civil Rights movement in America, and who is now in retirement in Argyllshire. He is a close friend of Paul Gillespie – a contemporary of his at Trinity in the ‘60s. He (Sam) also happens to be my brother, Aubrey’s, father-in-law. There’s a huge story there I’m going to write about when I get around to it.

Thanks Peter. Probably won’t get to Chicago (this time, anyhow!) as I am heading west and am currently in El Paso where I hope to get the bike serviced and a tyre change, before heading across New Mexico and Arizona into California. Onwards!

Great article Peter.

Thanks Colin. Love to you both from El Paso!

LBJ is a fascinating man. If you haven’t already read it, Robert Caro has written 4 volumes of biography “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” covering a period of 40 years. Volume 4, “The Passage of Power,” came out in 2012, and it’s a great read.

The fifth volume is due any year now, and is expected to cover Johnson’s first full year as president, 1964, and continue through the end of his administration in 1969 and his death four years later.Fans are afraid that Caro will pop his cliffs before he completes it- he us quite elderly!

Love to Paul and Melissa. X

Haven’t read Caro but, as I am now aware, he is clearly the man for the definitive scan of LBJ’s life and times. Greetings passed on and returned!

Sorry- typo. … pop his *clogs!

Thank you Peter for shining a light on LBJ who despite his many flaws, chiefly his disastrous Vietnam policy, left a record of reforming and progressive legislative change equalled by few Presidents. The are many parallels with him and that other often under appreciated President, Harry Truman. As Claire Duignan recommends, Robert Caro is the definitive and masterful biographer and Robert Dallek’s wonderfully titled “Lone Star Rising”. Underlining the scale of LBJ’s legacy which resulted in as many signature policy reforms as the Democrats arguably achieved collectively under all Democrat holders of the office of President, Barack Obama paid tribute at the LBJ library in April 2014 marking the 50th anniversary of the passing of the Civil

rights Act of 1964. Thank you for sharing Peter and for your insightful and fascinating travelogue of which I am an avid reader. Travel safely and well

Thank you Pat. An interesting man for sure….

Excellent writing. You captured the contradictions of LBJ. The strident anti- communism of the time blocked all critical thinking of that generation. It took a lot of protests in the streets to bring some reality to the war. Is Civil Rights efforts galvanized the Republican Party’s take over of Southern politics.

The lack of critical thinking in these times is no better. Confirmatory bias allows people to always to see their side as right and the other wrong.