March 7th 2023, Panama City.

Anyone travelling across the Americas by land, north to south or, like me, the other way around, faces a major obstacle in the middle. It is known as the Darién Gap — the gap being the fact that there is no road linking South and Central America through Panama’s southern province of that name. Anyone travelling north to south, will run out of road — literally — in a southern Panama town named Yaviza. Coming from the opposite direction as I did, the Pan American Highway, such as it is, comes to a shuddering halt in north central Colombia when it hits the coast at the Gulf of Darién, which is part of the Caribbean Sea. It doesn’t really matter where you stop, it could be at Necocli as I did or, a bit further along the coast, at the major Colombian port of Cartagena. Amazingly, there is no ferry from Cartagena to the Panamanian port of Colón, despite there being lots of shipping between the two places. One was tried a few years back and lasted but months. Why, I know not. There was also a German bloke with a yacht who specialised is taking bikers, and their bikes, on a sea jaunt between the two ports, via Panama’s San Blas Islands, with lots of sea food and snorkeling along the way. It looked like great fun but he’s upped stakes since Covid and headed back to Germany. Now the only sea option is to get together with others and hire a container and freight your bike from Cartagena to Panama. Quite a lot of bother to organise and it could take weeks to pull it off.

The only other practical option is air freight, which is what I did, using a company called Air Cargo Pack. Last Saturday, the bike went on one plane with several other bikes, while I went on a scheduled flight. The whole thing cost an arm and a leg — $1,200 for the bike, $65 at the Panama end, $100 for my ticket — but what can you do? And oh yes, there was also the $3 fee for a fellow to spray the bike with decontaminant before I could ride it away, a fee that paid for a certificate of quarantine!

It’s quite extraordinary that no road exists across the Darién and I am really sure as to the reason. After all, Central and South America are connected — by an isthmus. It is mountainous is parts (though not that high — one of the highest, Cerro Tacarcuna is just 1,874m above sea level) and where it is flat, it is basically a giant swamp. But modern road engineering could easily, if expensively, overcome such obstacles. Why that has not happened is unclear but it could be that governments on either side of the divide, and elsewhere, think that a connecting road would bring with it too many problems they’d rather not have.

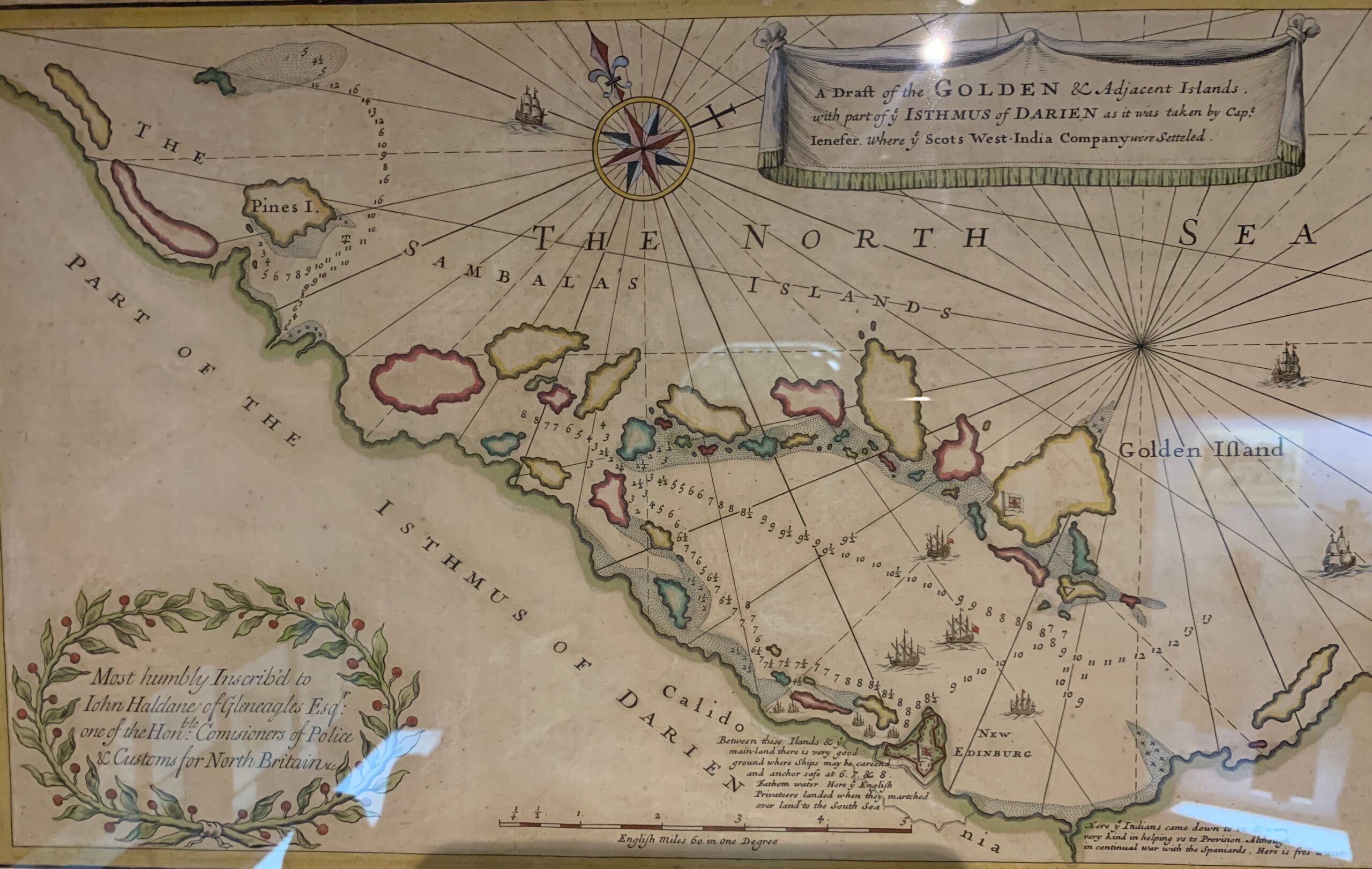

The story of the Darién Gap is itself fascinating and there’s a strong historical connection to our part of the world. Much is it is explained, in words and maps, in the Museum of the Canal in Panama City, about which I will write later. The story goes back to the late 17th and early 18th centuries and involved a group of Scottish investors. They set up a company, which they named The Scottish Darien Company, with the aim of establishing a colony in the southern part of the Panama isthmus. There was at the time no Panama Canal but the investors reckoned they could create an overland route, in effect linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and capitalising on trade between the two — doing in other words what the canal would achieve many years later.

The Company lasted just 12 years, from 1695 to 1707, but in that short time managed to, in effect, bankrupt Scotland. When investors were sought, there was something of a stampede: between February and April 1696, the funding target of £400,000 (about €60m in today’s money) was reached through investments of between £100 and £3,000 — all of the money coming from Scotland itself, and most of it from residents of the Scottish Lowlands. The ill-fated scheme sucked in approximately 20 per cent of all the money that existed at the time in Scotland.

Two separate expeditions set sail for Darién to set up the colony that would operate the overland trading route but both ended in disaster, with 80 per cent of those involved (a total of 2,400 people) dying within a year of arriving in the isthmus. The causes were many — tropical diseases, particularly Yellow Fever, and unsanitary conditions played a part, but so too did trade blockades (engineered by the English government and the rival East India Company) and a similar siege by the Spanish. When the company collapsed, the Scottish economy went with it, leaving Scotland’s lowlands (the southern heart of the country) in total financial ruin. There was uproar, not surprisingly, with riots, including the lynching of three entirely innocent English sailors, and financial scandal aplenty. The more lasting knock on effect was that resistance in Scotland to the idea that it should merge politically with England. This led directly to the 1707 Act of Union, creating the constitutional marriage we know today as Great Britain. (The Act of Union creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland came century later.)

Getting to air freight the bike involved a lot of palaver. Looking online for weeks suggested that Air Cargo Pack were a professional operation, a feeling confirmed by reading various biker chats on Facebook. After an email exchange with the company’s Maria, I arrived at their cargo terminal depot at Bogota Airport and waiting for me was Camilo, a genial minder and fixer. To get to that point involved a great hubbub with security guards and customs officials checking and frisking all comers and goers, policing access to what was in effect a bonded goods area. Once inside and taken in hand by Camilo, the bike was forklifted, with me sitting on it, into a cargo bay warehouse where it was examined and photographed, and all the luggage going with it thoroughly searched. I asked the police officer what he was looking for — drugs, he said. Happily my anti-cholesterol and hypertension pills didn’t count… but I was nonetheless frisked going in and out of the warehouse, as was everybody, all employees included. There was great interest in the bike, especially from where it came, and I was invited to plaster some of my special stickers onto the warehouse. Next it was off to the customs offices to get the bike officially signed out of Colombia, which took about two hours. But Camilo did all the work; I just had to sit there and observe the wheels of bureaucracy move as they do. Which is slowly.

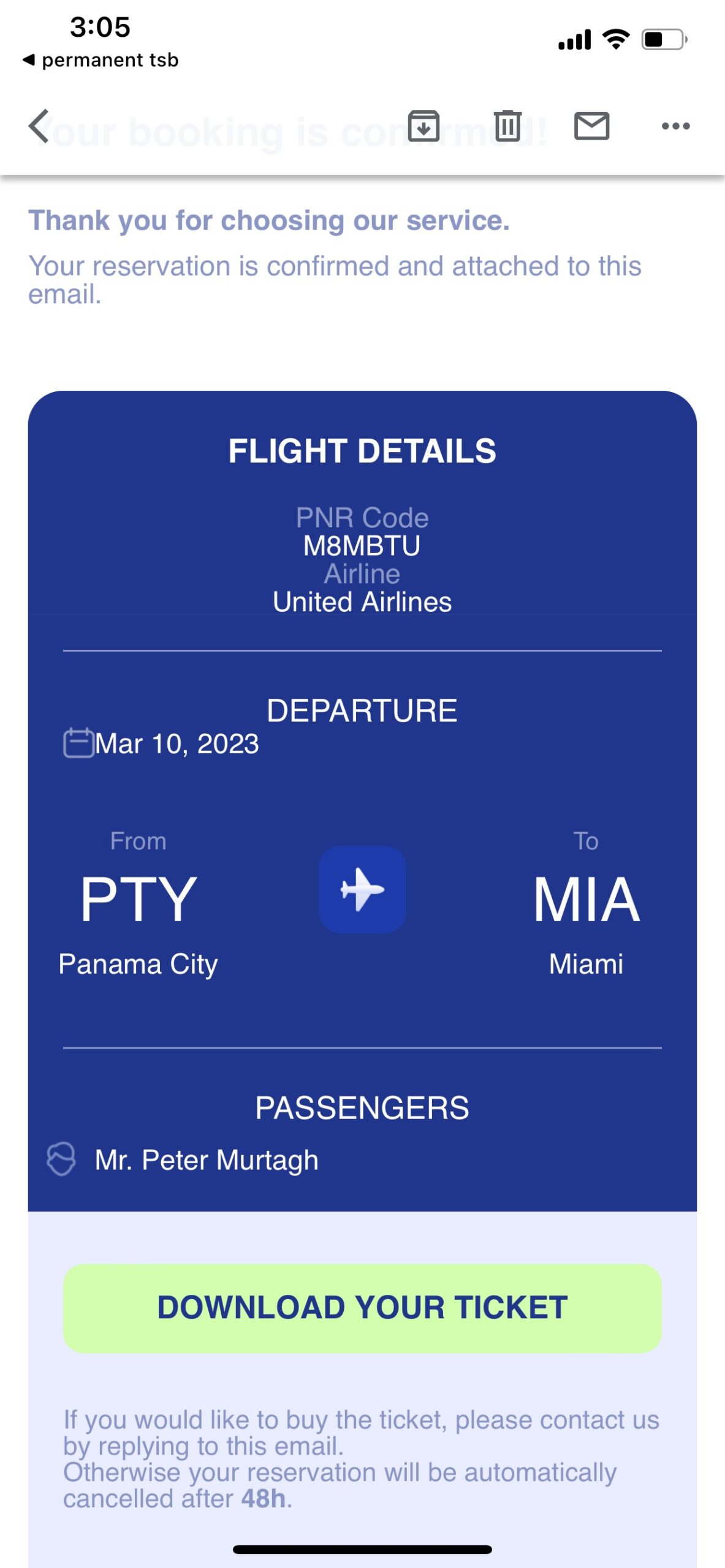

Going through the same process was a German biker, Jens Floss. He wondered whether I had got my ticket out of Panama before I tried to get in? I had not because, like, I was biking out. Better get one, advised Jens, else they might not let you in. The solution is to go to onwardticket.com — an outfit of which I had not heard — and buy a ticket to anywhere. It costs just $14 and, after a few days, onwardticket.com simply cancel the booking. You’d imaging that would play havoc with the airlines but there you go. And so, someone somewhere thinks I am going to Miami on March 10th.

And then came the bill: the nice lady at Air Cargo Pack said no, they don’t do cards — “solamente efectivo”, I was told. Cash only. It was Thursday afternoon and I had no idea if a bank would give me $1,200 from my Irish bank debit card. I had visions of my bike getting stuck in the no man’s land of an airside bonded warehouse for god knows how long as I grappled with banks in Bogota and Greystones. . . Panic was creeping in when, close to my hotel, I saw one of those currency exchange outfits and thought, well, you never know. And you know what? They did it — in a matter of seconds, $1,200 came off my card and was handed to me. I zipped back to the airport, paid the bill and thought: sometimes things just work out grand.

***

When something’s done and dusted, all paid for etc etc one often still has that nagging doubt — something’s gonna go wrong, I just know it. Something’s gonna go wrong. Nothing had gone wrong in getting out of Colombia — sure enough, the check-in lady asked for proof of my leaving Panama before she’s check me in and was suitably impressed with my booking to Miami — but that was the feeling at the back of my mind nonetheless as my taxi bore down on Panama City airport on Monday morning. The first challenge was finding Air Cargo Pack operation within Panama airport’s cargo terminal — not so much a single building as a sprawling mass of warehouses on the far side of the airport runway.

A hatch in the wall swished open. Passport! Passport handed in. $65! Can I see the bike first? $65!

And so it went.

A few minutes later, I was told that I must go to the aduana building (that’s customs), which was about a kilometer away. . . Another hatch and another pile of forms. But eventually a fellow in a pickup truck pulled up indicated that I should get in, which I did, and the pair of us returned to the swishing window. Eventually, the bike was forklifted from the warehouse out into the open, all wrapped in clingfilm and looking a little lost. But in one piece and all the luggage intact. I wasn’t allowed to do anything yet, however, as the decontaminater had to do his thing, which he did eventually — all gas mask and fine spray of chemicals designed, I assume to kill any noxious Colombian bugs etc.

It was a joy — and a relief — to be able to ride again. I sped off out of there and back down the highway to the city to plan the next stage and celebrate with some ceviche and beer. And if you are not into marinaded raw fish, don’t come to this part of the world.

Peter, a brilliant account of what must have been a very stressful episode …… the constant gnawing feeling that some Catch 22 trap is lurking just around the corner 😠 !

I remember my first ‘meeting ‘ with Darien over 55 years ago …. ….. the last line of Keats’ sonnet ….. “ Silent , on a peak in Darien “

There was always something magical about it.

A question : where would you be if you were looking west to the pacific and east to the Atlantic ? You’re there !

And the longest palindrome I ever came across : a man a plan a canal panama

Late night musings from Rosmoney ….. very best. Paul

Your recent posts have filled me with many different emotions. Sadness and fear for the migrants heading north especially after examining maps of the area. I shared your anxiety concerning the transport of your bike and belongings as well as your relief on safely rejoining them. The craziness of the patchwork quality of Panama City reminded me of being in places that both frightened and amazed me. Mostly I was impressed again by your ability to bring the events of your past few days to life and add colour to our days in a cold grey week here at home. The photos are also very enjoyable. Many thanks.

Thank you Wendy for such nice comments!

Great blog again; and fascinating history of the company which banjaxed Scotland. And yes, I saw that Miami ticket and thought WTF, is that madman Murtagh missing out the whole of Central America?

The Crucero Express ferry had been running on and off between Cartagena and Panama, but wasn’t when Clifford and I arrived in Cartagena in 2006, so we spent two weeks and $2000 organising for the bikes to be shipped to Colon, and we flew to Panama, took the bus north to Colon, and after two days of sitting around in the shipping agent’s office, got them out of the docks and left. Never been so glad to get out of a place than Colon. It’s aptly named.

Great blog again; and fascinating history of the company which banjaxed Scotland. And yes, I saw that Miami ticket and thought WTF, is that madman Murtagh missing out the whole of Central America?

The Crucero Express ferry had been running on and off between Cartagena and Panama, but wasn’t when Clifford and I arrived in Cartagena in 2006, so we spent two weeks and $2000 organising for the bikes to be shipped to Colon, and we flew to Panama, took the bus north to Colon, and after two days of sitting around in the shipping agent’s office, got them out of the docks and left. Never been so glad to get out of a place than Colon. It’s aptly named.

Interesting that you needed proof that you were going to leave Colombia. We weren’t, so that’s a new wheeze.

Thanks Pal! Fascinating place, the canal, for sure. Could have spent ages there and written more… but you could say the same for this whole journey. Every now and then I wonder what the hell I’m doing but something always pops up. Still can’t fathom the absence of a ferry between Cartagena and Colon. Maybe we should start one…..

Geoff: Being a bit on the slow side today it suddenly dawned on me who you are and that I have read all your travel books, in between fits of giggles and the odd guffaw. Like I said in my comment below I did that trip but in reverse. Bought a Yamaha XT600 from Razee Motorcycles in Kingston, RI (the proprietor was on the same racing team as the late Steve McQueen) in July 1997 and rode to Ushuia before looping to Buenas Aires for a full week on the tear over St Patricks Day with a Corkonian, funnily enough, called Lewis Carroll of all people. Then up through the Amazon by multiple river boats to Manaus before arriving in Caracas in May 1998. Somehow cracked a contract on an oil project (I work in Oil & Gas, that evil fuel!), met a nice girl and ended staying there for almost 2 years. Moved to Dublin (originally from Armagh), nice Venezuelan lady came over and we got married end 2000. We moved to Calgary in Alberta end 2008 with 2 young fellas and I have have been riding around Canada and the USA ever since (weather permitting of course); am hoping that I can meet up with Peter when he hits Canada so I can say hello. Anyway, as the man says “Love your work!”. Keep her lit – Sean

Peter,

What you have just documented eloquently is what I did in reverse back in 1997. Same kind of folk, same red tape, same shananigans – all we can do is take a deep breath and watch it unfold. In my case I got to Bogota all right but the bike…. well, it kind of went AWOL for a few days before magically turning up a week afetr I arrived. During that time I had fallen into some good / bad company (depending on ones definition) and was having a right bit of craic in Bogota; I was actually a bit sad when the bike turned up but I had needed to get to the end of Ruta 3 and out before it snowed.