June 28th 2023, Livengood, nr Fairbanks, Alaska.

Well, this is it, I guess.

I’ve reached Fairbanks and the last road calls. Would Jack London have felt “the call of the road” I wonder? Movement, the road, going west are all core themes of American literature and writing, and with them, that other great theme, dream and disillusion. I dreamt of this journey for quite a long time — if not this one exactly, certainly the idea of just taking off and going away for a long time, absorbing and coping with whatever is thrown at me. Or not. And in doing that, I have been blessed with an indulgent wife who has tolerated me and who I have missed more than I can say. Ditto my children. And the dogs. But nothing that has happened in the past eight months plus has disillusioned me — the opposite if anything.

All along the way, people have asked me “what have you learnt”? And my answer has been the same: “that people everywhere, all people, are mostly basically good and decent and kind, and just want what everyone else wants, or already has — a reasonable life and a chance to work and live in peace, and have a bit of a laugh every now and then, and they’ll go out of their way to help you”.

I’ve thought about this last bit, and not thought about it, if that makes sense. I’ve thought about it by way of wondering, day dreaming if you will, what it would be like. And I’ve not thought about it in the sense that I haven’t researched it that much, or planned it really at all. Like, I know where I am going — from Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay along the Dalton Highway, on an unpaved gravel road (hardpacked at best, mud at worst), which is 700+ kms long and serves the Alaska oil industry and not much more . . . apart from timber workers, bikers and other adventurous sorts who want to do it, well, just because it is there. I keep meeting people who asked where I’ve booked to stay along the way. And the answer is that I haven’t but I’m fairly confident that I’ll get in somewhere. I hope so because you can’t camp up there . . . because of the problem posed by polar bears whose environment is being destroyed by us and who consequently, and sort of counter-intuitively, seek closer contact with us for sustenance, either from garbage or, well, whatever else might be on offer, as it were. Hence no camping in Prudhoe.

I’d have liked to spend a number of days up there, trying to absorb the place and get a sense of it and the people who live and work there. I imagine them to be a mix of oil industry types, roustabouts, geologists, engineers, workforce managers, and others — oddball misfits who maybe work in the industry or just somehow hang around it in the way loose end people often hang around the edges of everything, plus indigenous, anti-oil or pro-environment campaigners, and then the people who know there’s a living to be made out of serving the rest of them — hostel or hotel people, and bar owners, if bars are allowed up there. Who knows? But if you are only allowed stay some miles back from the edge of the Arctic Ocean, some miles down the road from Prudhoe, and can only go there in a shepherded tour, I’m not sure I’ll get much of a sense of the place. We shall see . . .

I stay my final night before starting on the Dalton at a campsite called Northern Moosed. It’s a small place, a bit ramshackle but clean and run by a genial host, Ritch. $25 for a site and access to toilets and a shower. . . and his house-cum-office which has a kitchen, washing machines, TV and, crucially, plug sockets for charging my phone and laptop. After putting up the tent and settling in, I’m sitting in the laundry room writing and a new camper walks in. Are you in charge, he asks. No, I say, but look for the small fellow with white hair and a big Santa Claus beard. Ritch must have heard me because a few minutes later, he presents me with a post card. It shows a Santa Claus figure, who looks very remarkably like Ritch, wearing seasonal garb, sitting in a chair and making a list. North Pole AK, it says on the front — a reference to the town a few miles south that styles itself (rather ridiculously) as North Pole and is little more than a string of Christmas shops. It must provide Ritch with a seasonal winter nixer.

Round about 10pm, I get into my sleeping bag and go to sleep . . . and wake again at about 4am. It is 100 per cent bright as, at this time of year, the sun doesn’t fully set this far north. The guy in the pitch behind me, Gary, slept on the back of his flatbed truck and he’s up and about too.

“I’m from Idaho and I collect songs,” he says to me, “and I want to thank each and every one of you Irish for all the songs you’ve given me. I collect folk songs and you guys write songs about everything, everywhere you go. My favourite is from the 1890s, about miners in the Saw Tooth Mountains, complaining about everything — work, no women, everything, you name it!”

He says he’s heading south to Denali Mountain (aka Mount McKinley, 6,190m) — “the highest in North America”, he says — and then, who knows?

The Dalton begins about 80 miles north-west of Fairbanks. On the way, the countryside becomes more and more empty of people and dwellings. Near Fox, from where I set out, there’s a really messy property that is typical of its type, and not at all unusual in the States, in my experience. There’s stuff strewn everywhere in front of it, right beside the road — bar-b-queue bits and pieces, a ladder, bicycles and tyres, planks and chopped wood, and tarpaulins, several of them keeping out the elements. Still, I guess it is someone’s cosy pad inside.

Not far from there, I get my second glimpse of the famed Alaska oil pipeline. My first sighting was just before Fairbanks where it crosses the Tanana River via a suspension bridge built especially to hold it. It’s quite a sight. Now, on the way to the Dalton, I see it several times, snaking overground on stilts, through the countryside and the forests, along a pathway cleared especially for it. It looks very neat and tidy . . . and vulnerable to attack.

I pass a sign that says Arctic Circle Trading Post and turn in, with high expectations. Instead, I find myself in front of the Wildwood General Store, a log cabin outpost that is closed. Beside it is, weirdly in my opinion, a wooden shed proclaiming “Lemonade Stand”. It too is closed.

Just after Livenwood Creek and a timber roadway bridge, the Dalton emerges from the wilderness and is oddly small, or should I say narrow at the start. Not much wider than a single track. It has a jet black gravel top to it but one that seems well packed down and — famous last words — should be easy enough to ride. I take a selfie before setting off down it.

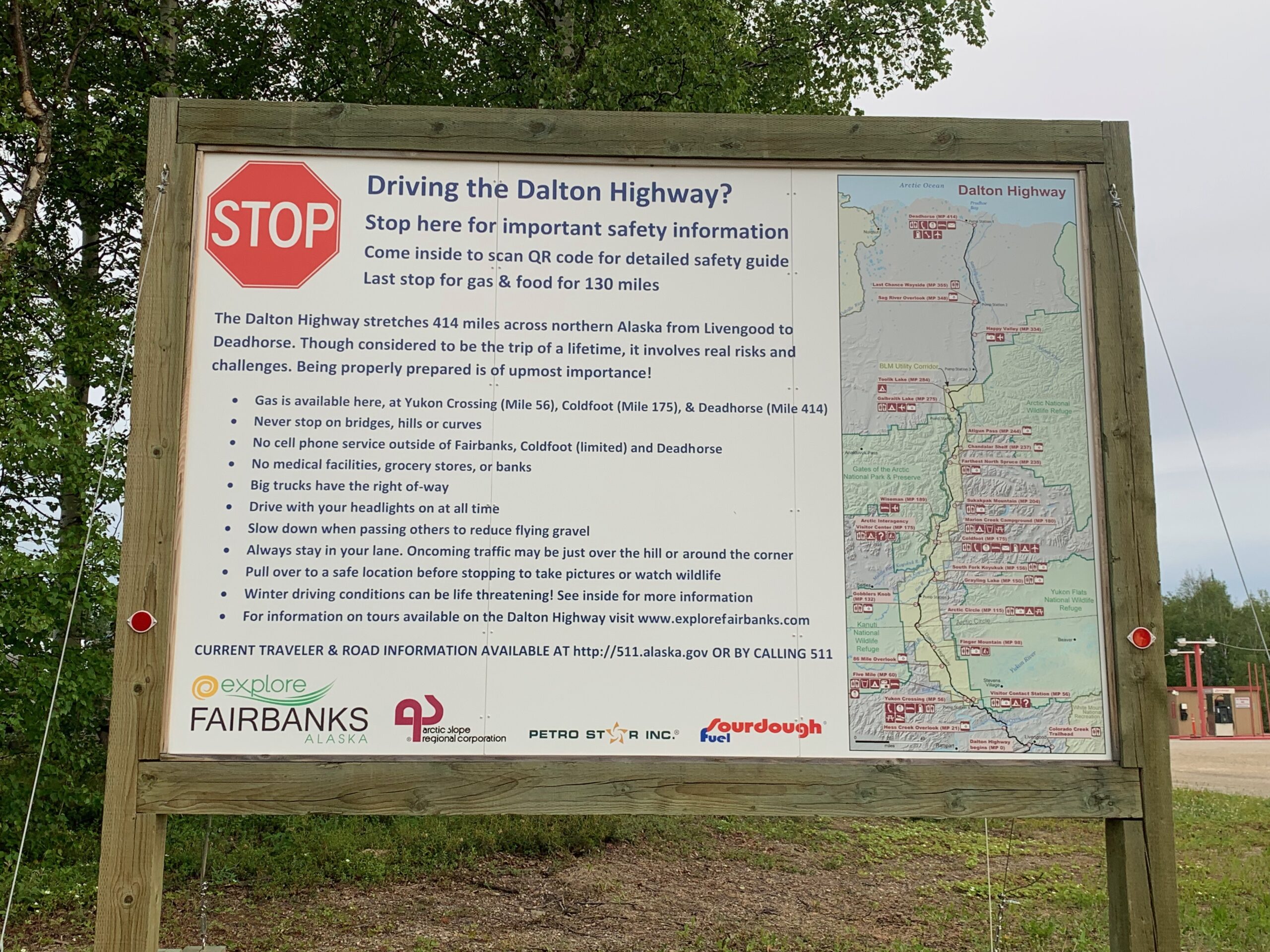

Coming out of Fairbanks, at a place named Hilltop there’s a big official noticeboard warning would-be users of the Dalton. Its 414 miles long (that’s over 700 kms), says the sign. “Though considered to be the trip of a lifetime,” it continues, “it involves real risks and challenges.” Big trucks have a right of way (so stay out of their way appears to be the import of that message), never stop on bridges or hills or curves. There are no grocery stores, banks or medical facilities. There’s no cellphone service outside of Coldfoot and Deadhorse, the last settlement just before Prudhoe Bay and the Arctic Ocean.

So you may not hear from me for a while. . .

First published by The Irish Times online on July 3rd 2023

Ah yes, I remember that sign, and going gulp. I stayed at Yukon Crossing before setting off for Gobblers Knob. Say hi to both for me, and if we don’t hear from you again, it’s been nice knowing you 🙂 Only joking: you’ll be grand!

Wow, into the last leg of your journey. We are pleased to see that you traveled to Vancouver Island, then way over to Jasper. You really went out of your way to see the great places Western Canada has to offer. We almost crossed paths with you again in both of those places! Enjoy the rest of your adventure. We will do a “cheers” to you when you reach your destination!

Your Canadian friends & cats

(met in Cape Disappointment)

Ah, thank you both — and the cats too! Final blog will be online in the next 8 to 10 hours! It was great meeting you and I hope maybe one day you’ll come to Ireland and I can show some of it to you. Best — Peter

Good man Peter

Actually my (surviving ) bike buddy and me are in Republic, Washington State having a fine beer at Republic Brewing on our way home to Calgary. We lost one riding buddy due to a bit of a tumble he took on Magruder Corridor crossing from Idaho to Montana on the Idaho BDR late last week – that was some hard core stuff that delicate folk from Armagh do not normally experience. Take her handy Peter and be safe up there.