April 30th 2023, Tucson, Arizona.

There’s a mountain that rises above Tucson, a little to the north and east of the Arizona city. It is called Mount Lemmon and, amazing to think of it as you swelter and bake in the heat of the city (it was 97 Fahrenheit, that is 36 Celsius yesterday — “wait’ll it gets 120 in the summer”, someone said to me) but a few weeks back, there was five feet of snow at the top of the mountain where there’s also a ski resort. On the way up — I needed some wild scenery to clear my head after the gun show — I stopped at Windy Point, a beauty spot with a view. It wasn’t windy at all but what a view! From Windy Point, the mountain falls very suddenly and very steeply to the plain below where sits the city. It’s a great view, it really is.

The granite rock is bare at Windy Point and there are great big boulders, some of which appear as though they have been piled one on top of the other to create a sort of sea stack effect. Around here, they call them hoodoos, a word that surely has to have been adapted from somewhere, or something, else? Anyway, there were a couple of guys getting ready to abseil down the sheer granite face of Windy Point and I was trying to position myself to get a good photo of them when I came upon this other guy who seemed a bit anxious.

“I got a proposal going on here,” he blurts out to me, as though that was the most natural thing to say to a stranger navigating his way across a very large spread of granite, with a very steep fall just inches away.

“Oh,” I think I said, as the penny dropped.

The young man had spread out on the rock a white tablecloth on which he had placed a cooler box, with its lid open to show a display of bubbly bottles, flowers and a retro radio set playing a carefully chosen song. He also had a friend with him who was on lookout duty. “She’s coming, she coming,” I think the friend said as he, and I, withdrew into some bushes.

Down the gravely path came a young woman in a white, knee-length flouncy dress and cowboy boots, directed by another friend, a female accomplice. The young lady rounded the corner, saw her boyfriend and the spread he had laid on, heard the music and immediately started to cry. He pulled a green ring box from his back pocket, got down on one knee and said what had to be said. They hugged and some family members nearby, his Mum and Dad, I think, maybe a brother or sister as well, cheered and applauded.

“I had my suspicions,” said the bride-to-be, “but I didn’t dare hope.”

It was a lovely, lovely scene and it really hit me because it was so normal, so natural and so in contrast to a lot of what I’d been seeing and thinking about here, as well as in Texas, since arriving in the United States from Mexico two weeks ago. It set firm in my mind something I’d begun to think about earlier in the day: I wanted to write about the other Tucson. . . the Tucson that is calm, normal, caring and concerned about the sort of things people ought to be concerned about.

It began when I returned for the second day to the Five Points Market and Restaurant, a place I had stumbled upon the day before. So named because it is on one of the corners where five roads intersect, the restaurant has a nice warehouse/industrial chic feel to it. There’s a small patio out front with trees to give shade and, inside, there’s lots of space in a large, completely open plan spread of tables and chairs, with coffee bar on one side and open kitchen behind. And all around are displays of wholesome food. Five Points also has something of a mission. It seeks, as it says on its website to “challenge the idea that profitability in the service industry necessitates the exploitation of labor, resources and agriculture”. To that end, the place pays employees a living wage (as opposed to have them depend on discretionary tips), pays for their health insurance as well and sources products locally. I immediately felt comfortable there in part, in suppose, because the other early morning breakfasters seemed to be “people like me”, as the saying goes. They spoke, dressed and behaved in a way that seemed normal to me. Reflecting my own prejudices, everything about the place and the customers said “liberal”, whereas so many other places said “conservative” or “Trump” or “angry” or all three. Five Points is on the edge of downtown, which is somewhat dominated by government and university buildings. It also nudges the older, original Tucson with its adobe, Mexican-influenced houses and, a bit further south, the less affluent Tucson where I saw people sleeping rough.

Where Five Points is there’s a bit of gentrification going on for sure. . . Starting my second day’s visit, I’m sitting at the service counter waiting for my coffee and eggs when the guy next to me starts to chat.

He’s Jamie Beatty and turns out to be general sales manager for Pacific Edge, wine and spirit distributors based in Phoenix, the state capital. He’s in Tucson for a mescal festival and we get on famously swapping mescal stories — he telling me about how the spirit produced in Sonora, just over the border in Mexico, is really developing and set to challenge the dominance of tequila as the national drink, and me of my experience with the small-time mezcal producer in Santiago Matalán. Jamie invites me to come later in the day to the industry show at Maynards, which I read earlier described as the best restaurant in town.

Just then, another fellow joins us. “Is that your bike outside,” he asks. Yes, I tell him and he’s amazed — “I couldn’t believe it when I saw the IRL plate,” he says — because he’s got a big connection to Ireland.

He’s Martin Coll, a Scotsman now living in Sierra Vista in southern Arizona, right down close to the border. He co-owns M&M Cycling and is a retired professional racer. “I used to race with Stephen Roche and Paul Kimmage,” he tells me. I tell him I know of them both, of course, and that Kimmage, being a journalist, probably knows my name, as I do his. Martin’s Glaswegian but his family have strong connections to Donegal. And so we chat about cycling and Ireland and places to see and things to do in Arizona.

Jamie and Martin separately have other matters to attend to, as do I — breakfast had arrived. Kevin, the barista guy, starts chatting to me. “We’re a little oasis,” he says when I ask him about Five Points.

Like the restaurant, there’s a bit more to Kevin than making coffee. He spends one day a week helping No More Deaths, a group that puts out water bottles in the desert on the Arizona side of the border with Mexico, so that illegal migrants at least don’t die of thirst. They also put out beans and socks and blankets (the desert can be ferociously cold at night). It is literally a random act of kindness. Much of No More Deaths’ work is done at Arivaca, a small Arizona village about 18 kilometres from the border, where the people “don’t want to be calling Border Patrol [the Homeland Security agency responsible for border protection whose officers catch illegal migrants] and there’s also a lot of gun-toting libertarian types there and they don’t want them too. So we go”, says Kevin. (Before speaking with Kevin, I had watched a local TV news report about another group that puts barrels of water out for migrants but has to contend with anti-migrant vandals who puncture them so the water drains out.)

No More Deaths originated with a Presbyterian pastor who wanted to help refugees from the civil war in El Salvador in the 1970s by offering them sanctuary.

A safe place for nature is the goal of Russ McSpadden, an environmental activist I met (at Exo, another chic cafe) the day before. I got to know Russ via social media about three years ago when researching this trip and really wanted to meet him. He works for the Center for Biological Diversity and spends much of his time monitoring the well-being of various species, large and small, and guarding public lands in the border region.

“The place has been under attack for a very long time,” he says of the border lands. “The wall is going to rewrite evolutionary history”. He points out that animals on different sides of the border “aren’t separate populations [but] we have separated them . . . [the authorities] do a lot of damage just in the construction process. This is one holistic landscape and it is just cut in half”. He says the fence/wall, which he says the Center has fought “tooth and nail since the Bush era”, cost between $20 million and $40m a mile to build. “It’s utterly ineffective — people come through it [by cutting the posts] and come over it. It’s just a wall and it addresses nothing, in my opinion.”

Animal movement corridors have been interrupted by the fence/wall. Species large and small have been effected, including the Black Bear, the Mexican Grey Wolf, Mule Deer, Jaguars, Mountain Lions, snails are other water borne organisms. The concrete footings of the fence extend some five feet into the ground. Because of human activity, aquifers have been damaged to the extent that “springs are now on life support”, he says. Later, I hear another environmentalist say that water used to be reached at a ground depth of 400 feet but now there’s no water until 1,000 feet down — an effect, I believe, of climate change. McSpadden tells me that on one stretch of the border, shipping containers were used to construct a solid metal “wall” 3.5 miles long which prevented the cross-border movement of jaguars roaming on over 800,000 acres of habitat critical to their survival. The containers have since been removed.

The Center uses the law — the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act — to fight its cases however, McSpadden says that post 9/11 emergency legislation, known as the Real ID Act “allows the Department of Homeland Security to waive all federal and state laws to push through wall/fence construction”.

“In other cases, they would have to research and make decisions [taking into account thee effect] on water, species and indigenous peoples, [but] all public safety laws you can imagine are waived,” says McSpadden.

Is he optimistic?

“When I get out into the wild, I’m optimistic,” he says. “I have cameras and in one canyon I can identify 12 individual mountain lions over several months. I’m optimistic because I have to be.”

Unexpectedly, the mescal fair — the 18th Annual Agave Heritage Festival, to give it its proper name — turns out to have a mission as well. (Its mezcal with a “z” in Mexico, and with an “s” outside.)

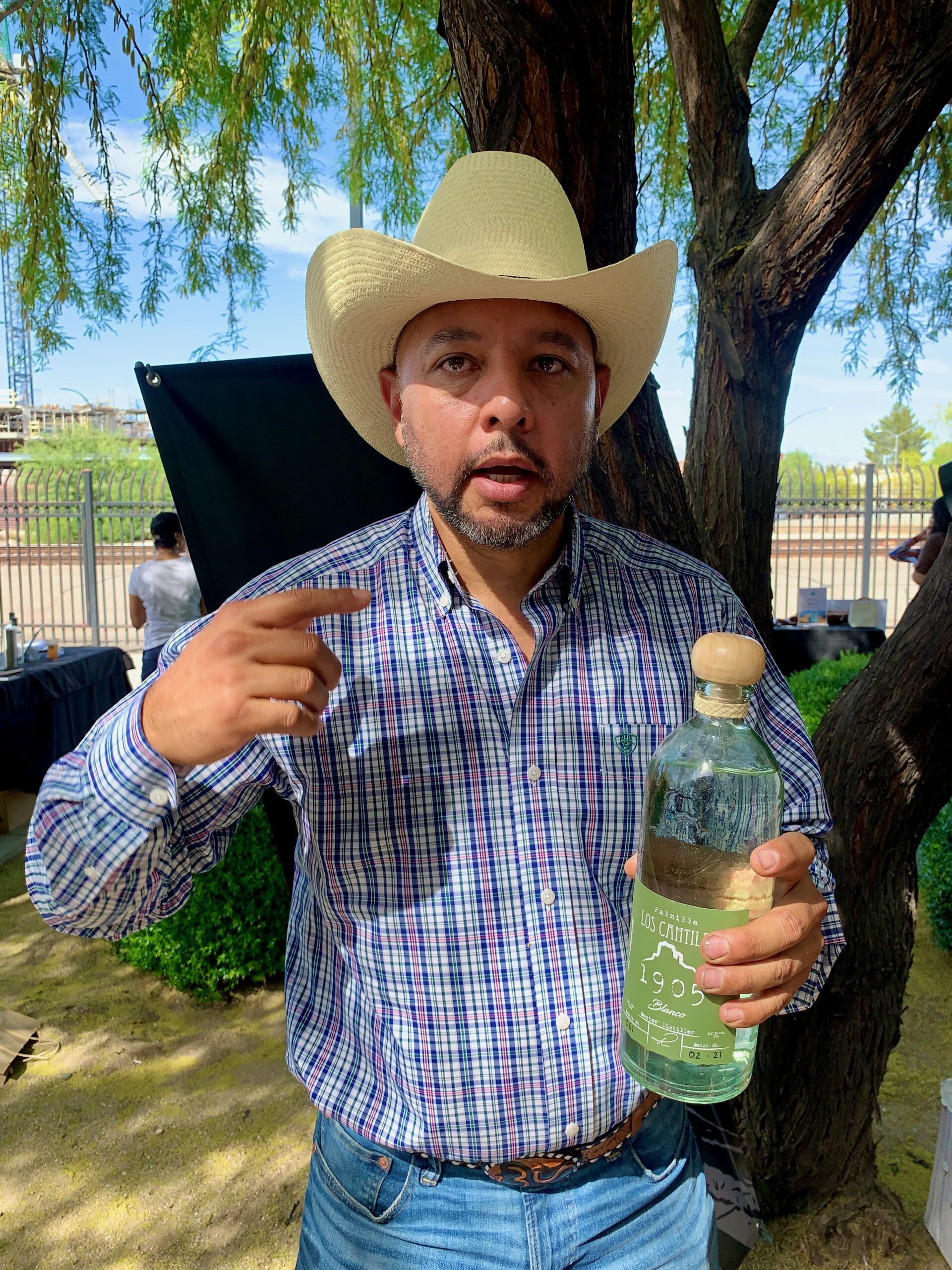

There are maybe a dozen stalls at Maynards on what used to be a train station platform, along with agricultural ecologist Gary Paul Nabhan and David Suro Piñera, co-authors of a book, Agave Spirits – the past, present and future of mezcals. Nabhan is also a Franciscan Brother while Mexican-born Piñera is a restaurateur and founder of the Tequila Interchange Project. I have a tiny sip of a Rancho Tepúa spirit, offered to me by Jamie but, riding motorbike, sadly have to decline any more. He, like everyone else here is full of enthusiasm for the Mexican spirit and its export potential. Near his Pacific Edge stall, the family behind Los Cantiles 1905 bacanora (like mescal, also distilled from the agave plant) are on a mission.

“We’re trying to rescue our culture,” says Omar Acuna (above, with a female colleague) from Nácori Chico, a small town in the Mexican state of Sonora. “The whole project is about trying to incentivise the new generation to take back what is about to be lost.” By which he means the myriad things than can be produced from the agave plant and other local resources. Todd Hanley, owner of Maynards, says the fair is about “trying to promote cross border business fertilisation with Sonora”.

In a question and answer session, Nabhan and Piñera extol the potential of mezcal production to fuse tradition and innovation. “It’s like a jazz ensemble,” says Nabhan. “They’re playing off each other.”

I set off California bound, invigorated by listening to people who are infused with optimism, not threatened by difference and “other”, and who don’t talk about barriers but of sharing landscape, culture and business opportunities.

The couple on Windy Point — Brandon and Cindy? She said yes. . .

You were in our neighborhood – Barrio Viejo. Sorry to not cross paths. Safe travels as you make your to Alaska.

Lemon is the best

Lovely story: especially after the gun fair!