June 25th 2023, Dawson City.

Dawson City is a real ramshackle place — half falling down, half done up, but for all that, fantastically attractive, for me at any rate. Bits of it are like every western movie you’ve ever seen. The roads are unpaved, just compacted gravel, mud and grey dust. There are no footpaths, as we known them. The sidewalks, where they exist, are boardwalks, sometimes buckled this way and that because the ground beneath them has given way. In the summer, the place can be baked by the sun and, next minute, drowned in torrential rains. In the winter in the snowy, icy silence, temperatures fall to minus 50 and everyone waits for that single moment in the late spring when the ice on the Yukon River, there since the previous November, cracks, unjams itself and floats away again. With the extremes of the weather, it’s a wonder the city’s timber and corrugated iron buildings survived a few decades, let along for over a century now.

The place today is great fun and full of history, of which it is making the best it can, having been created in a world that no longer exists but which remains enduringly fascinated by it. Built on a bend near where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon, on the only piece of flat land around — a frozen swamp, not far below the Arctic Circle — it grew from nothing almost overnight into a teeming mass of 30,000 people at the height of the 1890s Gold Rush. Mania is the only word that describes what it must have been like. It was, instantly, an American city in Canada but, despite the frenzied pursuit of money, in the Gold Rush year there were no murders and few thefts. Guns were banned and the RCMP, the Canadian police, were a visible, restraining presence. And then, within a few years, it was all over and the city shrank again, dwindling to as few as 300 people in the mid-20th century, locked in by winter for most of the year, but bouncing back and today nudging towards 2,000. In what a film narrator at the local museum describes as “one demented summer”, in Dawson City you could buy anything — from shovels and axes to tents, to top hats and silk dresses, oysters and champagne, and in Paradise Ally, and several other establishments, helped by madams such as Bombay Peggy, Madame Zoom or Ruby Scott, you could indulge your every fantasy. One lady was desired so much that she was bought for her own weight in gold. In Bombay Peggy’s, it is alleged (today) that one madam who went topless had breasts so large that she slung them over her shoulders.

The Gold Rush exploded like a giant Roman Candle, fizzled with a bright burning madness and then went out. Poof — gone! In the process of exploding with people, mostly men hungry for riches, the lands of the local indigenous people, the Tr’ochëk Hwëch’in, were completely overrun, prompting Chief Isaac to move the tribe downriver to a place named Moosehide. It is only in recent decades that they have moved into Dawson in numbers and the Canadian government has agreed a final legal text, recognising them and their long-standing, though hitherto largely ignored, rights over lands in the region.

Dawson today is still recognisably the place it then was, though without the really exciting, racy bits. All but one of the streets remain unpaved, so that when it rains, they are like a gloopy, slippery ice rink. Where there are no boardwalks, you just walk along the roadside. Many of the original buildings — hotels and bars — remain and function more or less as before, and the shops, many of them originals and with original name signs, all face front onto the street, and have those authentic tall square gable fronts seen in the westerns.

Some of the timber buildings are falling down, mainly because the permafrost, the permanently frozen ground, 20 to 80 feet deep that starts a few feet below the surface, has melted. This happens either because of global warning or something specific, such as the building sitting directly above it has generated heat and warmed the earth beneath it. For that reason, new or rebuilt and restored buildings are placed onto wooden stilt foundations, which themselves sit on a raised gravel plinth to distance the building from the permafrost.

St Andrew’s Church, a substantial timber structure built in 1901, is keeling over and has been abandoned to its fate, a slow motion death that one day will see it topple completely, if it is not knocked down first.

Not far away, two neighbouring buildings have fallen into each other and now prop themselves up. They are known as the kissing houses. Another building near my campsite on the edge of town, a two storey warehouse-style commercial structure sporting the name Mueller Electric, remains standing only because it is leaning against a cottonwood tree.

There are vacant sites everywhere, and some are just plain shabby. Uphill, at the back of the city, as the population declined, the forest reclaimed several vacated streets but you can still ramble around, finding ruins and bits and pieces of lives past. In the city, everything looks authentic and, for the most part, it is. The city fathers, the Canadian government and Parks Canada, the national parks authority, have ensured that what exists in Dawson today is not a Disneyland reimagination but something very largely authentic, albeit restored, preserved and curated. The street names tell a story of their own time: the avenues, running broadly north/south, start with Front Street which faces onto the Yukon, and then go the usual North American way of 2nd Avenue right up to 8th; while the other thoroughfares, running broadly west/east for maybe just a kilometre, have names locked in time — Albert, Duke, York, King, Queen, Princess and so on. The British influence in Canada is in general quite marked and noticeable, even in this most American frontier place.

A strong belief that gold in great quantity was to be found in the gravel of the creek rivers, that combine eventually to create the Klondike, whose very name became a byword for the Rush, brought about 1,000 miners into the area from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s, many of them from San Francisco. But there was no big find, no eureka! moment . . . until August 17th 1896 when three men, George Carmack, Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie were out hunting in Rabbit Creek and stumbled on a huge amount of coarse gold grit — a layer “as thick as cheese in a sandwich”, it was said. They staked their claim, renamed the valley Bonanza Creek, and got digging.

The outside world knew nothing until the follow-on winter had passed and a ship, the Portland, arrived in Seattle in July 1897 laden with gold. In that first year of mining, two tons of gold worth some $1 billion, was extracted from Bonanza Creek and others nearby — by panning, by digging down, using fires to melt the permafrost, and then digging horizontal tunnels. Light a fire, melt the ground, dig and bucket the result up to the surface for washing in water to reveal — hopefully — gold dust. Paydirt, they called it. When the Poertland docked and revealed her cargo, the whole west coast of America, and much further afield, went berserk.

Gold! screamed the newspaper headlines and some 100,000 people, many from California, set out for the Klondike in a mad scramble, half of them failing to get there, turned back by the extreme weather. Those that made it first went by boat, up the west coast to Skagway in southern Alaska, from where they set off on foot north-east and into the frozen Chilkoot Pass. The successful, hardy and really determined ones continued across lakes and down rivers to Dawson where some 7,000 home-made boats arrived within days of each other.

“Overnight, Dawson was the largest city north of Seattle and west of Edmonton,” says Lucy Welsh (pictured above in the restored Red Feather Saloon), a really knowledgeable, funny and engaging Parks Canada guide, one of several that lead visitors on walking tours around the town. I arrived from the south-east from Whitehorse, travelling along the Klondike Highway. About 10 kilometres outside the city, the first indication of something unusual are the huge mounds of river rubble in Bear Creek — about 15 kilometres of rounded stones, gravel and sand, piled high in mounds perhaps 20 feet tall on both sides of the road — the tailings of river dredging, long since ceased, and long since drained of any precious metal. The great mechanical river dredges came after the initial Gold Rush, of course. In the first flush of the Rush, it was panning, pick and shovel, and digging, first with the help of fires to melt the permafrost, then steam and then just plain water. Within weeks, much of the area’s natural beauty was ruptured as the landscape was raped. Thankfully as far as I could see, its mostly recovered.

Lucy took us to the bank that sprung up, The Bank of British North America, first in a tent and then a building, on a corner, just like banks everywhere love, looking sturdy, safe and trustworthy. It burnt to the ground several times (any gold inside was saved by the safe), fire being the bane of the city, until it was clad in corrugated metal sheeting, thereby creating in effect, a fire break between neighbouring buildings. It has been restored perfectly, with the counter, teller positions behind wire mesh and lighting just as they were a century and a quarter ago. The tellers took the little sacks of grit and gold dust the miners brought in and, out back, the contents were melted, burning out the impurities, and decanted into ingot moulds. Weighed, the miners were paid in cash, which the clever few squirreled away, or invested in the town (some bought hotels or set up other businesses), or took it south to San Francisco and bought mansions, while others blew it all in the city’s bars and brothels.

Not far from the bank is the fully restored Red Feather Saloon, complete with a long bar counter, foot rain and spittoons. Behind the counter, a triptych of mirrors doubtless reflected a packed bar most nights, a portrait of Edward, the then Prince of Wales looking, perhaps wishing he was there, given his reputation. Miners who brought their gold dust in with them, to show off or use as payment, sometimes allowed bar staff dip their finger inside as a tip, or just to let them feel it. In the process, tiny specks of dust escaped and fell to the ground, accumulating to such an extent that when the Red Feather Saloon, and other bars buildings in the city, were knocked or restored, traces of gold, reflecting the shape of the bar counter, were found in the ground beneath the floorboards, according to Lucy.

One of the few women to join the Gold Rush was Belinda Mulrooney (Irish surely?). She came to Dawson and make a go of it. Arriving with hot water bottles and bolts of cloth, she made enough money overnight, just by selling them, to open a cafe and start a cabin construction company. Profits from these enabled her to build a hotel, The Grand Forks. She became a millionaire in the process, the first Dawson woman to do so. Everyone in Dawson wanted to know what was going on in the outside world, as well as getting news from within the city, and so a newspaper emerged, the Dawson Daily News, which managed to keep going until 1957.

By the time the great surge of people arrived in July 1897, almost all of the claims had been staked and very few of the new arrivals actually struck it lucky. Most ended up working for others. Within a year or two, many drifted off elsewhere, some back south or into Alaska looking for gold there. Others stayed and grew old in Dawson, whiling away their time sharing memories and sitting on the boardwalks.

As the Dawson City gold ran out, in the early years of the 20th century the Canadian government tried to keep the place going by building a governor’s mansion and a grand post office, structural symbols of permanence, as they saw it. Today, the mansion is the town’s museum while the post office is a wonderfully restored exhibit within the city. Lucy takes us inside too see the wall of PO boxes, made of bass and bevelled glass.

A contemporary tradition has its roots in the harshness of the Gold Rush days. A miner named Louis Liken, who was also fur trapper and rum runner, got frostbite and, to prevent gangrene, he axed off his frozen toe and pickled it in a jar, leaving the jar under the floorboards of his cabin, for reasons he knew best. It lay there long after his demise, until the 1970s, when it was found by Captain Dick Stephenson who one evening at a bar — possibly a long evening, by the sound of it — dreamt up the wheeze of a cocktail involving the severed limb: The Sourtoe Cocktail. “You can drink it fast. You can drink it slow. But the lips have gotta touch that toe!” Thus was born a Dawson City tradition, a “must do” for visitors.

Sourtoe is a clever play on the word sourdough, which locally means a person who has been living in the Klondike for a time, as opposed to a blow in, as we would term it. The ghastly drinking process involving the cocktail is alive and thriving in the Sourdough Saloon in the city’s Downtown Hotel.

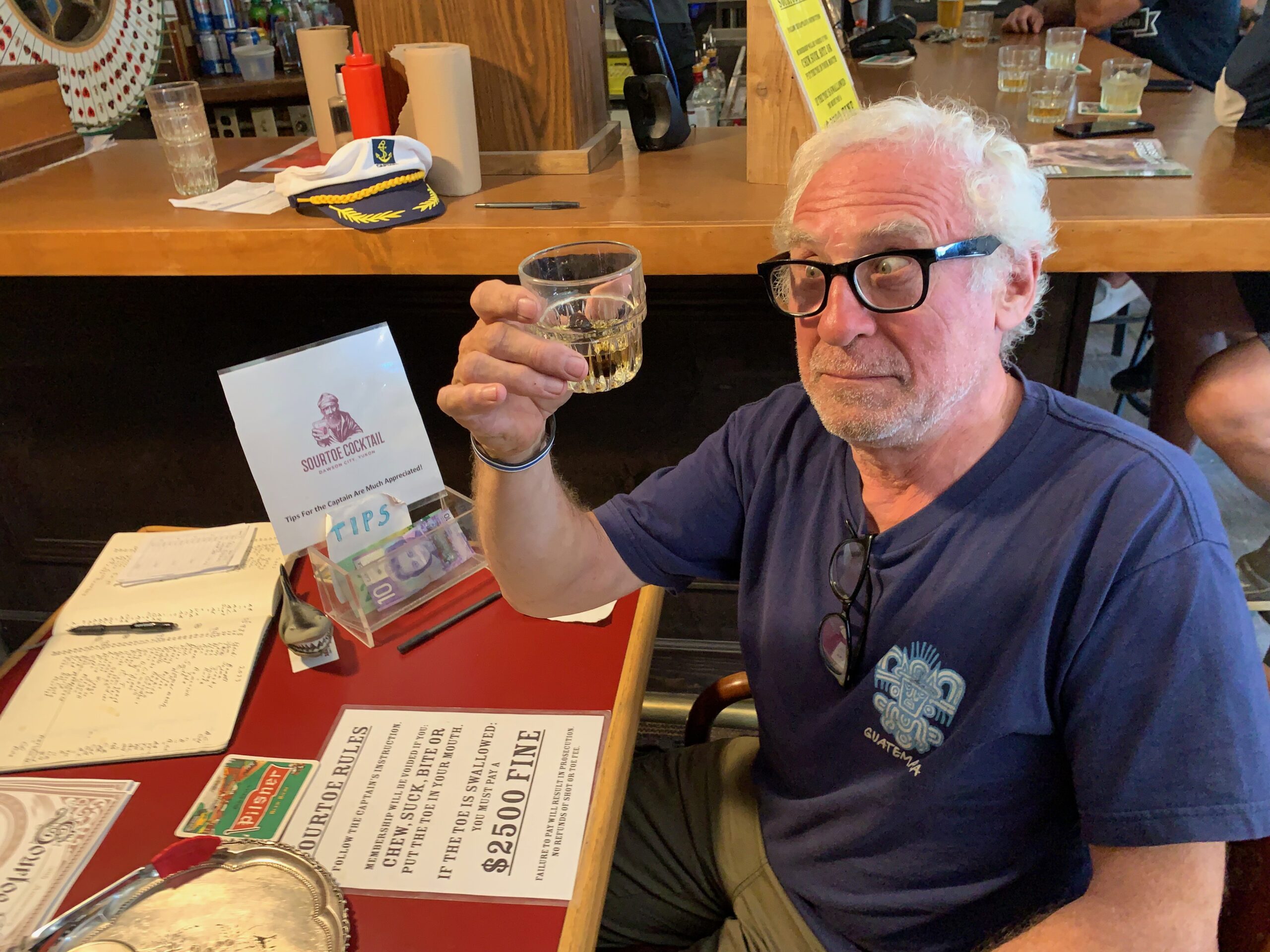

Every night from 7pm on, 75-year-old Terry Lee, with a salt and pepper beard and looking like an old sea dog, plays the role of Capt Dick, initiating new members into the Sourtoe Cocktail Club. Initiates must down a shot of liquor of their choice, in which the severed limb has been dropped their lips touching what does indeed look very like a small, pickled and very old, toe.

My turn arrives as my name is hollered across the bar and I sit down in front Capt Terry, successor to Capt Stephenson who died in 2019. “Chonas a tá tú,” Capt Terry says in a flash. “Tá me go maith,” I reply with, in my view, commendable speed and lack of surprise. It turns out that Terry used to work in Glenealy, Co Wicklow, for a man named Don O’Sullivan, trying out various tree types from Canada, pines mostly. Before that, Capt Terry worked on ships but, burnt out as he says himself, he then got into forestry which pitched him into a State forest exchange programme in Ireland. He’s been in Dawson on and off for 44 years. “Some people come here to escape,” he tells me. “Some people come here to see and experience and return home. I am in the latter group.” And so when the snows come, Terry heads off to the Philippines. . .

With a theatrical flourish, Capt Terry uses a pair of tongs to picks a black and slimy looking thing from a plastic box, and drops it into my glass of Yukon whisky, uttering the traditional edict: “Drink it fast or drink it slow but your lips must touch the toe”.

I did, and it did — a slug-like but rigid thing bounced off my upper lip as the Southern Comfort-like liquor slipped down nicely, easing my discomfort. And as a result, I now have a certificate verifying that I am member number 105,966 of the Sourtoe Cocktail Club . . . and with that, I was outta there!

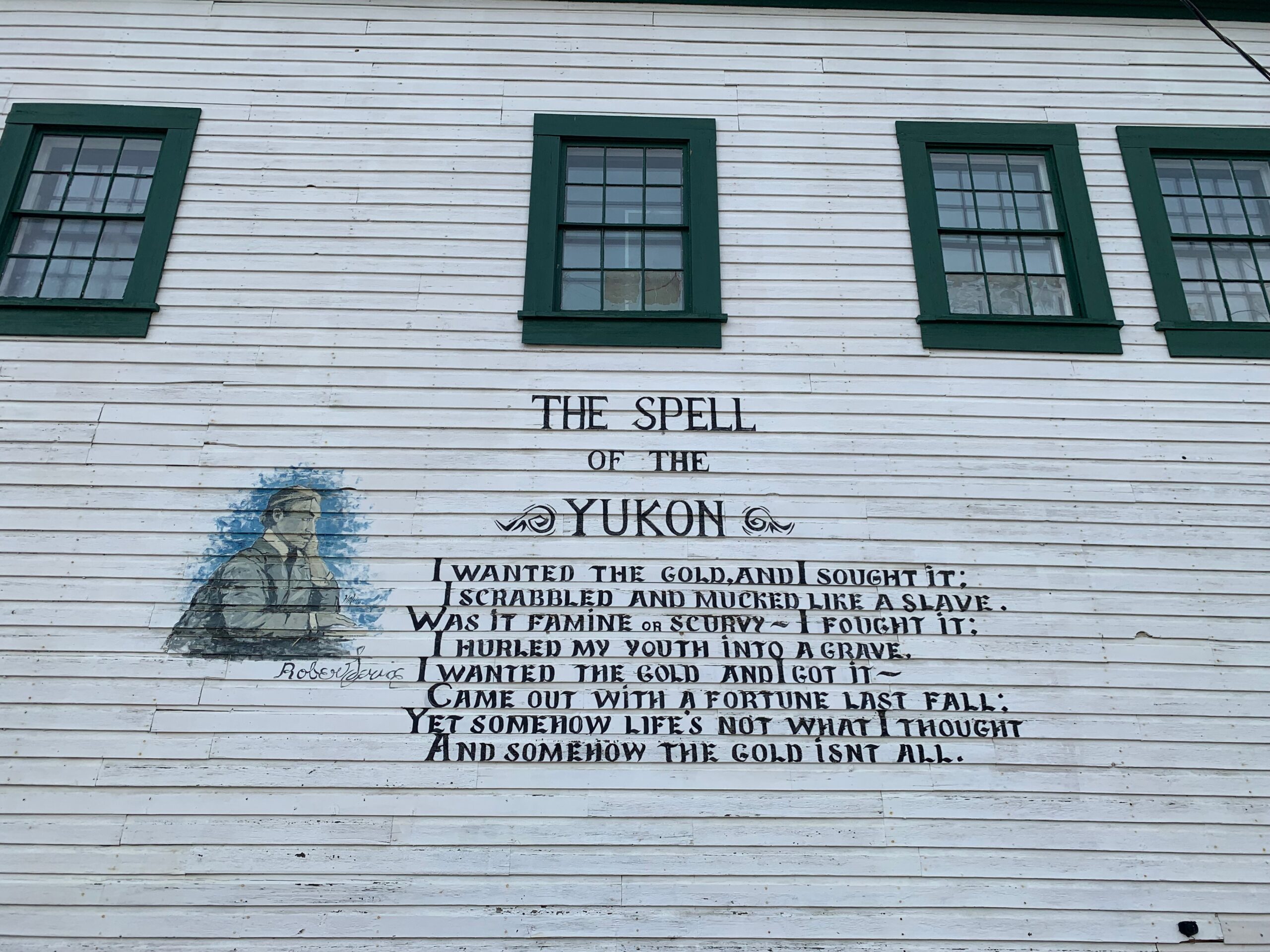

Jack London was 21 and rather aimless in San Francisco, working on boats and thinking about writing, when he caught the Klondike bug. He headed to Dawson with the others and spent a winter in a log cabin in Henderson Creek. Today, the cabin has been reassembled in Dawson, beside the Jack London Museum and a little way down from another cabin on 8th Avenue, one rented by the banker-cum-poet Robert Service who also fell under the spell of the Yukon. For Service, The Yukon had “beauty that thrills me with wonder, It’s the stillness that fills me with peace”, as he wrote. He is remembered in a gable mural downtown.

London’s museum is a small wooden building of one room filled with photographs of the man and dedicated to his memory. The tiny cabin beside it is fascinating: it is a single room hovel, with two raised wooden lath beds covered in caribou pelts and a small wood-burning stove.

Joann Vriend, a potter, gives talks about the man and his time in the museum and early on reminds us of the opening lines of White Fang, one of his great animal stories, in which he refers to the “savage northland silence”. London spent a winter in the Creek, panning for gold buy failing to find the riches he craved. Instead, he turned to his natural talent, writing, and became the first American author to be a millionaire — “but he never had any money,” said Joann, “he liked to live large”, as she put it rather well. He cranked out at least 50 short stories and magazine or newspaper pieces from1900 until his death, from kidney failure and alcoholism aged just 40, in 1916.

I feel certain that his story, To Build a Fire, had an influence on Hemingway’s The Old Man And The Sea — the themes are just too similar for that not to be the case. London certainly fired my lust for travel, and for this part of the world, when I read him as a teenager and when I look now at The Yukon landscape, or on Alaska’s, even in the summer, I know exactly what he meant when he set White Fang in “a vast silence [that] lay over the land”.

With all the travelling you do it beats me how you manage to have time to write about your adventures in such detail. Dedication no doubt. Wishing you safe journeying onwards.

Great read Peter! Amazing it still exists with such a short period without freezing temperatures! Certainly reminds me of the old cowboy films!

Great piece. Fascinating place, Dawson. I wonder if Buffalo Taylor, who was fire chief and head of everything, is still there. He showed me around in 1991, and was still around in 2017: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/vintage-firetruck-from-yukon-restored-in-blenheim-1.4207931