March 19th 2023, Coyolito, Honduras.

I was stopped once more by the police in Nicaragua and, on this occasion, they could not have been more pleasant, friendly and professional. I am happy to be able to write that because it proves, again, that even in a society where something is clearly rotten, individuals can and do act with integrity if they so choose.

It was just before the city of Leon on the road NIC-12A, which is the main route from Managua to the frontier with Honduras. Two uniform police with two back-up para-military style colleagues armed with assault rifles were operating a static roadside inspection of vehicles. The road was straight and I was sticking rigidly within the speed limit. They flagged me over and I obeyed, turning off the engine and removing my sunglasses as I did, and greeting them with a smile and a big hello. I showed them my papers and soon the conversation relaxed into friendly banter about the bike and what I was at. They accused me of nothing (and had no grounds to accuse me of anything), and made no demands. I gave them some of my journey stickers, they posed for a photo (one of them was busy at the time and so is not in the shot) and then they waved me on my way, with their good wishes. An incident as it should be and should not be worthy of comment but, sadly, this is Nicaragua.

I’m now well out of the country but these are my reflections. They are naturally impressionistic in the main and I don’t claim to be an expert on the place. I stayed at a hostel in central Managua, catching up on rest and writing in the main. I visited just two areas in the city.

The first was the Huembes Market which is pretty much bang in the centre. I have a thing about markets, mainly because of their colour and energy. They’re full of people (if they’re any good) and usually there’s a lot of banter and leg pulling, especially when, as a visitor, you stick out like a sore thumb. A good deal of the humour and warmth in Dickens’ writing comes from his portrayal of street sellers and they’re cast from the same mould as market stallholders.

I can honestly say that I have never been in a market with as diverse a range of items on sale as the Huembes. It is a vast covered market hall that spills out onto the surrounding streets and pavements and, while fairly shambolic and run down, it works. There’s everything you’d expect to be able to buy in a hardware store — everything for the home or workshop. There’s cobblers and guys operating sowing machines to repair your clothes. There’s nail bars and hairdressers, shoe shops, watch shops, jewellery shops, and clothing outlets with colourful walls of T-shirts, blouses and trousers all suspended from elevated positions to catch the eye of would-be buyers. There’s stalls selling pulses, rice, seeds, spices and oils, baskets and coloured rope, threads and yarns. There’s areas for meat — pork, chicken and beef — fish and, of course fruit and veg. And here too are the underdogs’ underdogs — the lottery ticket hawkers, the beggars and those living out of the mounds of rotten fruit and veg that pile up as the day wears on. Outside of a nail bar, a woman gave her caged parrots a shower. . .

There’s ramshackle restaurants ready to serve the thirsty and the hungry. In the meat and fish area, there was also a lady selling live iguanas, their legs tied to stop them escaping. Two had lost the tips of their tails, why, or rather how, I am not sure. The wretched animals were on an aluminium tray, looking warily at anyone paying them any attention. And why wouldn’t they? — they ‘re about to sold onto a dinner plate.

Cuanto? I asked her.

Doscientos cincuenta, she replied — 250 Córdoba, about €7.

Es bueno?

Si, si, she said emphatically, es muy bueno.

I’ll just have to take her word for that.

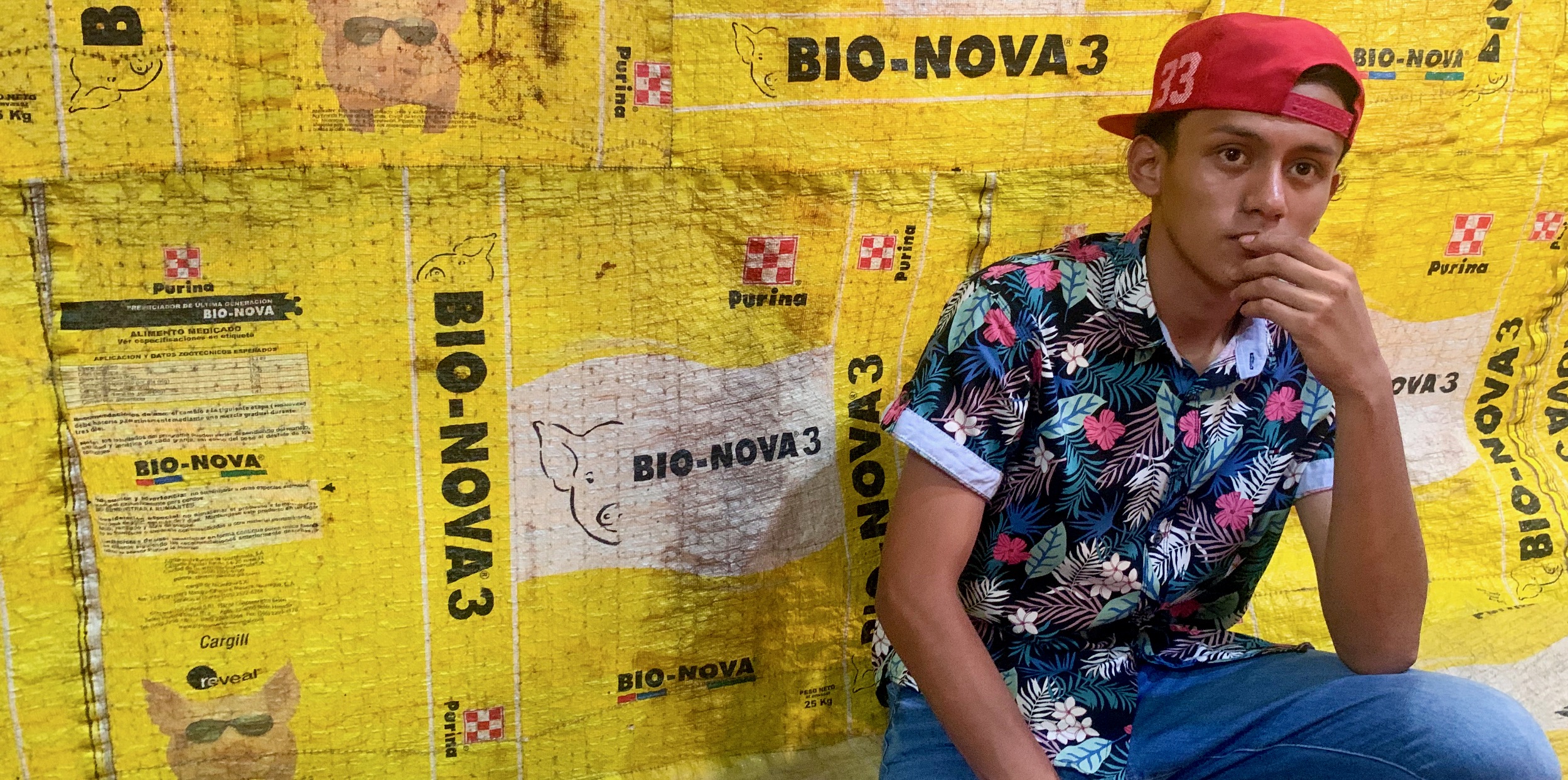

What endeared the place to me was the reaction of stall holders to me when I engaged with them, often wanting to take their picture. Almost all said yes and smiled, or acted the maggot in some playful way. There was an unforced happiness and it was lovely to see it at work.

The following day, I went downtown, down towards the lake, on the shore of which the city sits but does not take full advantage of, at least not in this location. There’s a grand avenue leading there, Avenida Bolivar, a big fat road such as many cities have, a thoroughfare that bisects and which becomes a sort of display case for much that is important to the inhabitants. About midpoint along the avenue, towards the lakeshore end, there’s a major roundabout which is dominated by a huge, perhaps 10 meter tall, representation of Hugo Chavez, the late Venezuelan leader whose policies, and their vigorous pursuit by his successor, have wrecked his country and sparked the largest mass exodus of people in modern Latin American history. Here, it seems, he’s a hero.

Towards the bottom of the avenue in an area called La Bolsa (The Bag) where one finds a cluster of the sort of statement national buildings one would expect to find — for example the National Theatre, named after the poet Rubén Darío, and the Palacio Nacional, the national museum which contains objects and artistic representations that all nations use to tell their own story.

Facing the museum is the House of People, built with a donation from the government of Taiwan and used as a presidential palace until 2000 and thereafter for government functions but closed now, allegedly because of high running costs.

And here too, completing three sides of a quad, is the forlorn spectacle of a ruined cathedral, the Catedral de Santiago Apóstol, wrecked by an earthquake in 1972 that killed 10,000 people. It is modest by cathedral standards but quite pretty, even in its broken down state, and must have looked lovely when whole. The facade has a giant slogan across it: “todo con amor todo por amor” — all with love all for love.

On the facade of the museum are two giant-sized posters. One shows a man on a horse, with the words Sandino and the slogan “estamos cumpliendo!”, which translates as “we are fulfilling”. The other poster shows a picture of a man, and proclaims “Carlos: Avanzamos en la Revolución!” — “Carlos: We advance the Revolution!”

Both posters are signed, simply and in signature script form, Daniel ’07.

Sandino is Augusto César Sandino, a revolutionary opponent of the US occupation of Nicaragua, who was assassinated in 1934. He is the inspiration behind the Sandinista guerrilla movement, the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (the FSLN), that today rules Nicaragua. Carlos is Comandante Carlos Fonseca, former secretary general of the Sandinistas who was killed in 1976 fighting the family dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza Debayle. The Somozas ruled Nicaragua, with an iron fist and strong US support, from 1936 to 1979.

Daniel is Daniel Ortega, the increasingly autocratic and repressive President of Nicaragua, who rules alongside his wife, Rosario Murillo, who has the title vice president. Ortega sees himself as the contemporary torchbearer for all that Sandino embodied and is president of the political party the FSLN has become.

The final side of this quad, the side facing both the square and Avenida Bolivar, is Parque Central, a very pretty and well-maintained public open space in which the heroes of Nicaragua’s current political establishment are honoured. The setting includes the mausoleum of Comandante Carlos, with an eternal flame and surrounded by the red and black flag of the Sandinistas. The little park really is pretty — a knot of pathways lined with privet hedging and flowers in bloom. But, after a while there, what was most striking — to me at any rate — was the absence of people. It was Saturday afternoon, a time for shopping and for strolling, a time for sitting on benches in the shade of a tree and for eating ice cream, for chatting with friends or cuddling a lover. A time for relaxing and enjoying one’s surroundings in an agreeable setting. And yet there was almost no one there; there’s a strange emptiness about the place. . .

When I asked people in Managua how things were, the most common one word answer, after a little thought and some apparent hesitation on their part, was “regular”. The context of my question was invariably related to the political climate and/or the economy — in other words the state of the country. Regular used in this context translates into English roughly as “Meh, OK. . .” In other words, things have been worse and they sure could be better but, like, I’m doing the best I can. I have checked with several people and they all agree, “regular” as an answer to this question translates into that sort of meaning. So things are not great here for many people but they’re wary of talking openly about it.

A young-ish woman, who I won’t name here but met in a hostel in a near neighbour of Nicaragua (to where she was heading, incidentally, to work on a farm) said that in her previous visits there, she had met older men who wanted to go to Ukraine to fight with the Russians against the Ukrainians, and younger people who would not talk politics except when inside their own homes.

In my lovely hostel in Managua, they don’t have water during the day, just a piddling trickle from one kitchen tap. “You better take a shower now,” said Michael as he checked me in when I arrived very early one morning, “because the water will be off soon.” A day or two later, I watched as they tried to hook hose pipes onto the water circulating around their small swimming pool, directing it to an elevated tank that fed the hostel’s shower system. The operation was not entirely successful! “The aquafers are drying up,” Michael added.

Nicaragua has a severe water supply problem. Because of climate change, the water table has been lowering which means that tapping the aquafers for supply, which feeds the cities, has to be rationed. The story is slightly different in rural areas where people rely on surface water — that is, rivers and lakes — for domestic use, ie washing clothes and for drinking. But surface water has become severely polluted, due in large measure to there being no proper sewerage system. Rural people defecate into holes in the ground and the resultant deposit is allowed simply to soak away, leeching into the soil and ultimately into rivers and lakes.

Over 20 years ago, the US Army Corps of Engineers surveyed the situation and concluded: “Given the rainfall and abundant water resources, there is adequate water to meet the water demands, but proper management to develop and maintain the water supply requirements is lacking.” Not enough has changed since then, it would seem. The provision of clean water must surely be one of the key imperatives for any government but in this, the Sandinistas are less than successful.

When Daniel Ortega emerged as an international figure in 1979 after the last of the Somoza’s fled the country, he was lionised by many on the left. He was young and handsome and there was a whiff of the Che magic about him. Since then, apart from the 1996 to 2006 decade, he’s ruled Nicaragua, as president since 2007, winning elections the fairness of which have been questioned by the opposition and, increasingly, by foreign observers. Despite retaining power at the polls, Ortega has become increasingly autocratic and thuggish, cracking down on anti-government protests, particularly in 2018 when 360 people were killed by security forces, in a series of incidents collated by rights groups.

Perceived and actual opponents are stripped of their citizenship and cast into exile. In February, 222 political prisoners were deported and 94 people, including some of the country’s best known writers and journalists, were stripped of their citizenship. Two of the 222 were past presidents of the country’s business association which earlier this month was shut by the government.

Ortega, his family and supporters, some of them external, including the Miami-based Mexican oligarch Ángel González, own or control eight of the country’s nine TV channels. Aged 77, Ortega shows no sign of preparing to leave the political stage. At his behest, constitutional term limits on the presidency have been abolished. Yesterday, March 20th 2023, the US State Department said there were now credible reports about arbitrary killings and torture. The department’s human rights report for 2022 pointed to “numerous reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings”.

For much of its existence, Nicaragua has been plagued by meddling by the US, behaviour that inspired Sandino, emboldened the loathsome Somozas and is now used by Ortega to justify his own anti-democratic behaviour. It struck me as odd, therefore, to see so much of Managua looking like a giant American mall. The life-style, retail and architectural influence of the US is very striking — whether it be the malls and their parking lots, the style of hotels, or the type of outlets that seem to flourish. There are signs of it everywhere — including a branch of Walmart near my hostel, or the profusion of US-style fast food outlets. And amid them all, one sees regularly people travelling the city by horse and cart. . . something not uncommon in Dublin well into the 1960s.

It’s no surprise I guess that the place is in a bit of a state, God help it. Maybe Ortega’s just another regular guy to rule Nicaragua, doomed to failure, doomed to repeat the mistakes of his predecessors and be the oppressor of his people . . . doomed, ultimately, go the way of the last Somoza.

I have amended this piece having been over generous to Ortega in terms of the fairness, or otherwise, of Nicaragua’s elections.

It is not true that the integrity of Nicaraguan elections has not been questioned. I was a member of the EU electoral observation team during the elections of 2006, and my colleagues and I were told by a FSLN functionary that we were wasting out time, that the results were being decided by the Ortega controlled election Commission in Managua. Since then there have been widespread accusations of fraud and high levels of abstention given the pre-ordained nature of the result.

Hmmmmm. I think, on reflection, you are correct. What I was trying to communicate (but failed) was that the actual voting was OK, when clearly there is much wrong otherwise — treatment of opposition generally and during campaigning, gagging the media etc etc. I’ll amend accordingly. Thanks for pulling me up on that.