December 7th, Puerto Octay.

Alexander (32) from Switzerland used to sit in an office where there were computers on every desk. Most of them had the sort of screen savers popular almost everywhere — photos of beautiful, often dramatic landscapes that would appear whenever the computer wasn’t in use but remained switched on.

He was head of a section in the purchasing operation of one of the country’s major retailers. His job, which he liked, was sourcing and buying cameras for all the retailer’s outlets across the country.

Flavia (29) worked in marketing for Remax, the US-based estate agency operating globally, including in Switzerland. She too liked her job.

The pair of them lived in Zug, a town some 30 kms south of Zurich. “Thirty thousand people and 30,000 companies,” says Alexander. “It’s Switzerland’s tax haven!”

But earlier this year, the pair of them resigned from their jobs, set aside €50,000 and headed to Cancun in Mexico and have been on the road ever since. In Central America, they climbed Guatemala’s Acatenango volcano before heading to Panama, from where they sailed to Colombia. Since then, they’ve been through Peru and Bolivia and are heading to Ushuaia in southern Argentina.

And after that? Who knows but they’ll be gone for a year. They are travelling mainly by bus, though when I met them, they were using a hired car.

“We want to see the world ourselves and not just online or on a TV screen,” explained Flavia.

It was fitting that I ran into two Swiss people, at a campsite in Puyuhuapi, a small fishing settlement of fewer than 1,000 people on the edge of a fjord. As I have moved north along the Carretera Austral, through Patagonia and into Chile’s lake district, a Germanic influence has become more and more apparent. Beside the campsite, for instance, is Hostería Alemana, run by Otto who has two flagpoles in his front garden — one sporting the Chilean flag, the other a German one.

The Austral is now also mostly paved — thank God. Just before Puyuhuapi the road slips between mountains, the (appropriately named) Cerro Elefantes and the Queulat National Park range, which has a hanging glacier. On one short and very steep unpaved stretch, there are no fewer than 14 hairpin bends — a nightmare to negotiate on gravel that in places is as deep, and therefore as unstable for motorbike wheels, as a dry riverbed.

I failed on two of the bends, toppling over but without serious damage or injury, because I was moving so slowly (which was perhaps part of the problem). Later, at a petrol station in La Junta, I met four Argentinian bikers heading south and into this stretch. Three were riding suitable bikes, a Royal Enfield Himalayan, a Ducati and a Benelli. But one was on a Harley B Rod (think Batman movie), a long, low-slung streak of jet black US highway testosterone, a machine less suitable for what they were facing into I cannot imagine.

One puncture more (repaired for €10 after a ferry ride and night’s sleep in Hornopirén) and I’m in lakeside Puerto Octay, simply because it was on the map and I didn’t fancy stopping in Puerto Montt. Like several small towns in this region, it has a pronounced German feel to it — a feel rooted in the design, shape and style of the buildings, and occasional other things, like signs for German beer that use gothic lettering.

In a cafe, a beautifully converted former workshop and shoe store, Pauline, the French-born owner notes that I am a biker, and says I must contact her friend, Francisco Maturana, who has several bikes, she says, and is just up the road, opposite Anita’s restaurant.

“I’m sure he’ll show you,” she says. “He’d love to meet you.”

Several motorbikes turns out to be at least 130 — an utterly amazing collection, including several seriously rare machines and all of them lovingly restored. Inside the entrance to a large wooden barn (like something from the film Witness), the visitor is met by three bikes displayed vertically, one above the other, against a wall. There’s a 1890s pedal bicycle with wooden wheels that are sheathed inside rubber, and then, below it, a 1909 250cc Alcyon, an early French-built machine, and finally one of Ducati’s revolutionary Bimotas, a strange-looking bike with front forks replaced by a joint, front and rear suspension, slung under the engine.

Francisco and the extraordinary Bimota

“It is very unique,” explains Francisco, “there were only 29 of the first edition made.”

The aim of the display is to show the evolution of two wheeled transport. Francisco is very knowledgeable on the history and development of bikes. Between 1910 and 1940, there were about 2,000 makers but many did just one part of a bike — the frame or engine or wheels — allowing other companies, or individuals, build machines from multiple sources. In its day, Ariel of the UK was as famous as Norton. “But they didn’t survive,” as Francisco says.

He quite funny as to national characteristics translating into the machines.

“The Italians build bikes that fall apart,” he says, “but the Italians [and he puts on the accent] say ‘eyes but eess beautiful, no?’. The Germans build bikes that work and when they don’t they fix the problem. Same with the Japanese because if there is a problem, the maker kills himself.”

And the English? I ask. “The English……” his voice trails off into a miasma of evident frustration as he explains the problems of British insistence on imperial measurements, which means double sets of tools. Everything changed, he maintains, with Honda and the introduction of the electric start, among many other innovations others were forced to emulate. But the English were too slow and so most of their once iconic brands disappeared.

The entire collection will form the core of a motorcycle museum and family fun activity centre park on the edge of Puerto Octay. For Francisco (53), supported by his wife Loreta (pictured above), the whole thing has become a passion and is now his life’s work (facilitated by the proceeds from the 2014 sale of his online real estate business). Next April, the permanent home for the motorcycle collection, which is emerging on the grounds, project managed by Francisco who trained as a civil engineer, will open . . . all going well.

Part of the workshop display

But for now, everything is in the modern wooden barn, itself a beautiful building. The ground floor opens into a restoration workshop, offices and a range of machines on display, culminating in my own BMW R1200 GS Adventure — “the only bike for Alaska”, says Francisco. And he knows: he did the trip a few years back, north to south, the opposite direction to me.

Part of the upstairs display

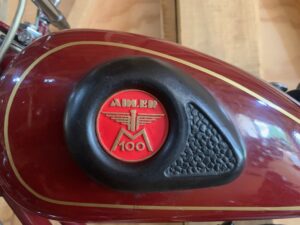

Upstairs, large picture windows look out to the surrounding lush countryside. And the enormity of the collection becomes clear. It includes a Belgian FN 1913, a 1926 Henderson (like the one used in 1912-1913 by Carl Sterns Clancy, first man who ride a bike around the world, starting in Dublin) and an extremely rare 1928 500cc, pressed steel Opel (known as the Rocket). There’s a 1929 James, a 1958 Adlerwerke 100, a 1958 Horex Imperator, a TWN (short for Triumph-Werke Nürnberg, a plant run by the German engineer who founded Britain’s Triumph), a 1935 Royal Enfield, a 1950 Benelli, several Harleys, Nortons, Triumphs and BMWs.

The pressed steel Opel

The BMW Afrika Korps sidecar

There’s a 1938 Excelsior, a couple of BSAs, AJS, Matchless, Suzuki, Kawasaki, Honda, a 1960 Panther and a 1959 Motobi, along with several smaller bikes and scooters. On and on it goes. . . There’s a collection of sidecar bikes including a 1930 Harley, a 1956 Zundapp and a 1943 BMW Afrika Korps. And the collection also includes one of the outrider cops who accompanied Bill Clinton when he visited Chile in 1998.

To put it mildly, this is not what one expects to find in a little town like Puerto Octay but boy, is it worth the stop. Anyone interested in motorbikes, in motor engineering, design and development, from the ungainly and clunky to the sexily sleek and dangerous, will love this place. For me, biking is less about the machines and very much more about the freedom they deliver, and about just going to places and meeting people — people like Francisco and Loreta and the generosity they display when someone just arrives, unannounced and unexpected.

But if the machines are what does it for you, this is deffo a place to visit!

Good piece, chum! Puerto Montt was where Gary and I got our hands on the bikes, from memory. Buen viaje!

Super story Peter…Puerto octay..who would have believed it.

Let them know I will be swinging past for tea soon.

You’d love it Ken. He’s a terrific guy and deeply serious about what he’s doing. The bikes are only bloody amazing. . . Unfortunately the videos I did, two with him, were too long for the website but I’ve put them up on Twitter and am trying to do the same on FB. I’ll give you and young O’Kelly a private viewing when I return!

Hello Peter, it was so nice meeting you! With Francisco we hope you´re having a wonderful journey!

Hi there. Nice meeting you too and, yes, I am having a wonderful time — like of riding, lots of interesting things to see, and people to meet, and lots of work. But that’s what I like! Hope you are good too…. Best — Peter